Time to read: 6 min

We’re seeking out the best hardware companies to help uncover the many challenges, lessons, and philosophies behind hardware product development.

In this week’s Hardware Spotlight, we had the chance to sit down with Tyler and Lei, co-founders at DrumPants. They founded the company with the vision to pioneer a more natural way for humans to interact with their devices from their bodies. We chatted about their first prototype, development challenges, and advice for bringing a product to market.

What inspired you to develop DrumPants?

Tyler: Ever since I was a kid I always wanted a musical instrument I could carry around with me. The first thing I dreamed up was a pocket guitar with a telescope neck you could unfold and then have a little guitar to play around with. Then when I was in grad school in 2006 I was with some friends and we were just tapping on our bodies, having a pants jam of sorts, and I was inspired to start working on the first prototype as a school side project.

Was there a specific problem you saw that DrumPants could solve?

Lei: With the advent of the iPhone and iPad there’s over 300 music apps available but musicians and DJ’s are still using these large, bulky hardware pieces. For the companies producing the hardware, their version of innovation is just a smaller version of what they already have. So we wanted to attack the problem from a different angle. Building off of what Tyler and his friends had hit upon in grad school we saw that tapping on your body is a really natural way to control midi sounds and use the motions of drumming without the equipment.

So how did you go from this idea in your head to the first prototype?

Tyler: For the very first prototype I took a giant yamaha midi keyboard and wired up my pants directly into the circuits where the keys should go. Then I took all the guts out and put it in a plastic case which I then put into a backpack that I carried around. I also had these gloves with wires in them so when you hit the pants it completed the circuit.

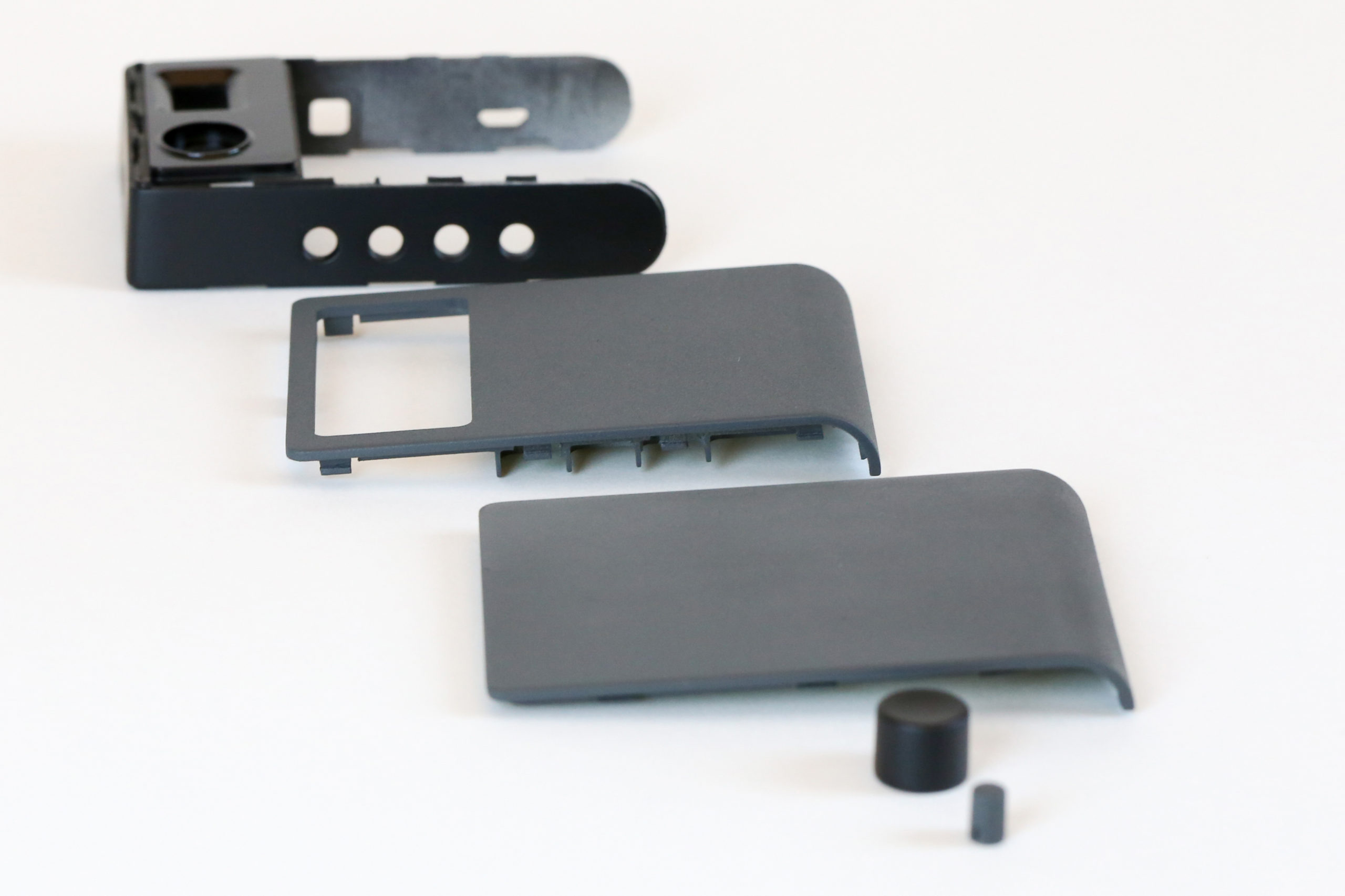

Lei: (laughing) When I first met Tyler he was like, “here it is!” and it was literally sensors duct taped to his jeans. So we started with sketches and really thought about how the product would be used. For example, the case we have now is grey but the original design was white. The reason we chose to make it a dark color is because when you’re on stage you don’t want a bright object that could be seen by the audience. We then used very low fidelity mockups using foam board and glued the pieces together to figure out the thickness of the case and get a feel for the product by putting it in our pockets. We wanted to test everything.

Which technologies did you use to go from the backpack to your next prototype?

Tyler: First we used a PIC controller and then moved to Arduino once it came out. Then we brought an electrical engineer to the team who created the first custom board and built the first iteration of the housing. After our Kickstarter funding we also hired an industrial designer and a wearables developer. Then we did a series of 3D prints. Really shitty, cheap 3D prints — nothing like Fictiv.

When we said what we needed, Fictiv knew exactly which machines and which types of plastics to use.

What was the difference between Fictiv and the first 3D printers you worked with?

Lei: When we said what we needed, Fictiv knew exactly which machines and which types of plastics to use. And on top of that there is a huge world of difference in quality between those first 3D prints and ones Fictiv did. When people see this (holding up the first prototype casing) and you tell them it’s a 3D print they are very forgiving of it because they think the final one is going to be way better and that all the little issues are going to go away. It’s not real to people. But a Fictiv printed case actually feels like the real thing. It’s so tangible.

The vision of the product changed every time someone put it on and I saw them use it in a way I didn’t expect.

What were the main considerations and challenges in designing your product as a wearable?

Lei: We had to play around with different shapes to figure out which ones would be comfortable to wear. When testing one of the first controller iterations people really liked it but said it was too long and stuck out of their pocket — a similar problem that the iPhone 6 is having right now. Also, we originally we wanted users to be able to open the case to change the batteries but then we decided that we really needed to get rid of any inefficiencies taking up space.

Hacker Note: Secrets await the curious engineer who hacks into the board. (Disclaimer: you might not be able to put the case back together again.) ((duct tape!))

How did user testing inform your designs?

Lei: That saying, “get out of the building and talk to your customers” is so true. Constantly we had musicians come in. We reached out on twitter and also asked people to recommend friends who were musicians. We had professional drummers, people who had played once or twice — little kids even. Everyone’s feedback was immensely helpful in creating a product people truly wanted to use and could use with ease.

Were there any features added because of the way someone used it?

Lei: We originally made the drum pad out of velcro because we thought people would just want to stick it on their clothing. But then people kept asking for a way to strap it onto themselves. Because of that we changed the way you could attach it and added the straps.

DrumPants can be used to control other applications beyond musical/midi ones. How much are you focused on musical applications vs non-musical?

Lei: One of the big innovations we’re working on now is figuring out which devices people will want to control from their bodies beyond just musical ones. We’re looking for ways to apply the technology we have been developing to everyday interactions in order to help people simplify their daily lives.

Tyler: For example, you walk into your house and if you have one of those Phillps smart bulbs you have to take out your phone, unlock it, find the app, open the app, find the button to turn on the lights and then turn them on. You’ve just completely negated the intended convenience of the smart bulb technology. A standard light switch is so much easier than that! But if you’re wearing a controller that knows you’re in your house and that it’s nighttime, then you can just tap on your body and it knows to turn on the lights. That is actually quicker than finding a light switch because you always know where your pocket is.

It’s all about building a great team and delegating to the people who are experts.

What advice would you give to other makers and engineers looking to bring a new product to market?

Tyler: It’s all about building a great team and delegating to the people who are experts. I started off with the mindset of, “I’ll just get a TechShop membership and make all these prototypes myself!” which soon turned into, “wait… so I’m going to sit at TechShop for 6 hours and wait for this print to get botched?” It’s worth it to pay someone like Fictiv to do it for you.