Time to read: 9 min

Remember the clunky, brick-sized, beige-colored cell phones the 1980’s used to carry around? That’s what today’s environmental sensors remind Will Hubbard of. Will is the COO and co-founder of ChemiSense, a new player in the environmental sensor space that’s working on an air quality sensor that’s smarter, sleeker, and cheaper. And definitely not beige.

It all started in an industrial engineering class at UC Berkeley, where an undergrad majoring in entrepreneurship named Will and a grad student in chemical engineering named Brian happened to sit next to each other. The two got talking and before long Brian’s research that he’d done over at CalTech on new chemical presence detection technologies sparked an idea. That idea became ChemiSense.

Excited about changing the world of environmental sensors, Will and Brian founded the company before the course ended and went through an accelerator, the well-known Plug and Play in Sunnyvale. Still in the pre-seed stage, they are already being courted by serious industry customers.

In this Spotlight, Will shares with us the joys and challenges of redesigning a manufacturing process that’s been around for decades—and raising the bar for an entire industry.

Deconstruct, Define, Differentiate

“In the larger scheme of things,” says Will, “we’re pretty passionate about the environmental sensing platform as a whole; about improving environmental sensing across multiple factors that have been holding back a lot of progress and innovation.”

It’s one thing to recognize a market segment ripe with potential, quite another to build a successful company—and one that redefines a mature sector no less. As with any new, ground-breaking product, Will and Brian had to nail down what differentiated their sensors from entrenched competition.

“We felt we could do orders of magnitude better in terms of performance and price, and launch a new wave of environmental sensing. So, that’s where we started.”

“To us, it seemed environmental sensing was stuck 50 years in the past,” Will explains. “The sensors on the market today are complicated, physically large machines. They can only detect one or maybe two elements or chemicals—say, carbon monoxide or nitrogen dioxide—and you have to handwrite all of the measurements to record them. They don’t detect elements inherently—you need to get microcombustion and all sorts of scientific acrobatics going just to get a viable reading. And then there’s the extremely high price point: $3,000 and up for an air quality sensor. We felt we could do much better, orders of magnitude better in terms of performance and price, and launch a new wave of environmental sensing. So, that’s where we started.”

Pushing the Limitations of Scope

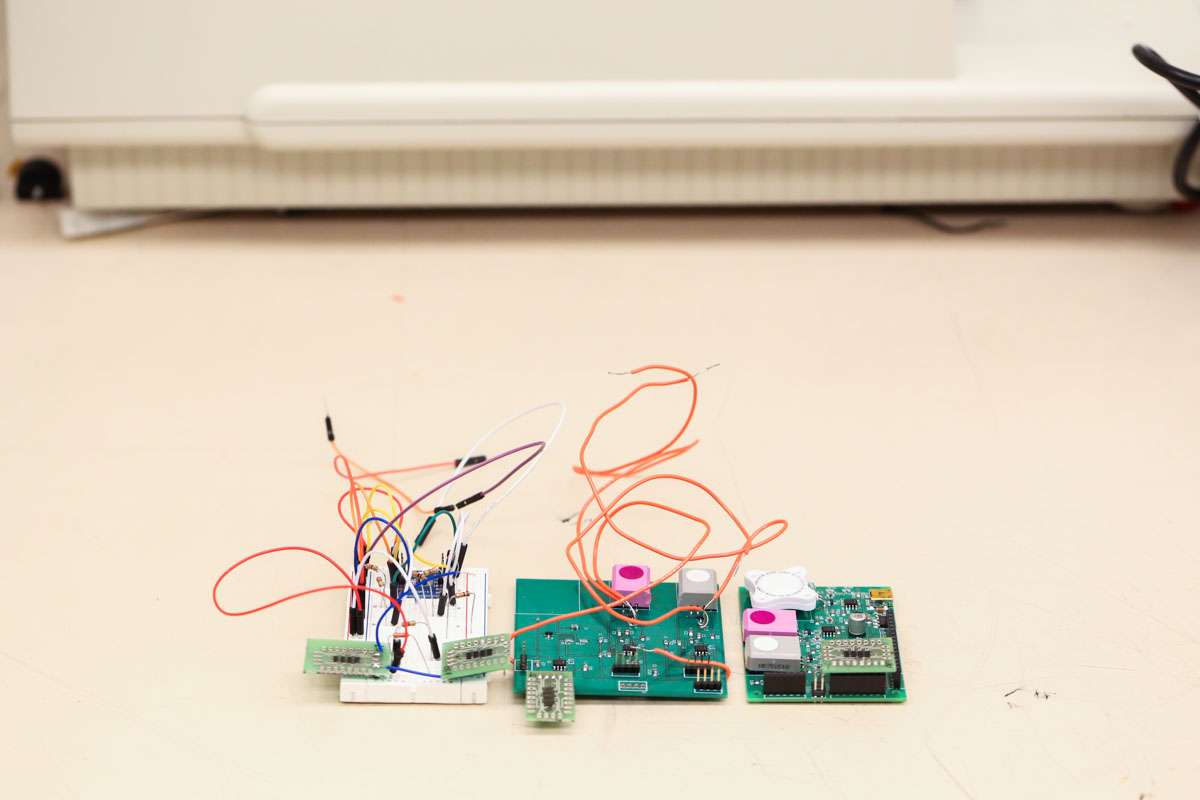

The first limitation of traditional air quality sensing that Brian and Will worked on was detection scope, or the range of elements that a sensor is able to detect. ChemiSense sensors can pick up intel on three areas of air quality: comfort and health-related elements such as air pressure, temperature and humidity; indoor as well as outdoor chemical pollutants; and two categories of particulate matter according to micron size.

You know, all the things we can’t see or smell but sure can tell when we react to them: pollen, dust, dander and all manner of other allergens.

“We could see clearly which areas were good, which ones were moderate and which ones were dangerous to your health.”

Then there is visible—in some countries tangible—pollution like smoke, soot, and smog. And the worst offenders, chemicals like benzene and formaldehyde (What? Really? Yes, really.) that you can’t smell, see, or react to until years later when they’ve built up in your body, because they’re small enough to pass through your lungs and into your tissues.

All this is ChemiSense territory now.

A Truly Sensitive Sensor

The second limitation the ChemiSense team tackled was detection sensitivity. Will explains: “We can capture not just the off-the-chart levels people typically look for, but all the fluctuations in air quality that naturally occur because… well, it’s air.”

Case in point: Brian and Will took a little road trip around the Bay Area recently, their car hooked up with three sensors. They recorded air quality measurements as they drove, and created a heatmap of the findings.

“We could see clearly which areas were good, which ones were moderate and which ones were dangerous to your health,” reports Will. “In real time and in specific locations. Like the Dumbarton Bridge, where things tend to smell funky. Surprising to us, the whole Palo Alto area was significantly worse than San Francisco. As we passed by the SFO airport, our sensors reported that air quality dipped.”

“There are so many different factors that go into air quality and our devices detect them all.”

Will and Brian compared their heatmap against the Federal government’s air quality report, which said the entire Bay Area was green (i.e., all good). Translation? ChemiSense sensors are much more sensitive and provide more actionable data. With real-time heatmaps and historical trend and plume analyses, says Will, “we can provide people and communities with a solution they can use. For example, if you want to go out for a jog or roll your car windows down during your commute, you’ll know which route to take. That’s our long-term vision.”

The heatmap exercise was so convincing that the Harvard Medical School is now working with ChemiSense on air q-mapping the greater Boston area.

Size Matters, but the Other Way Around

Next up, size. “A gas chromatography sensor is the size of a table and a traditional air quality sensor is like those 1980’s cell phones,” says Will. “Who wants to carry that around?”

Still, the company’s devices are no smaller than the palm of an adult’s hand. Wearables are all the rage, so one wonders why a hot new industry-disrupting company like ChemiSense would steer away from wearables and focus on stationary sensors.

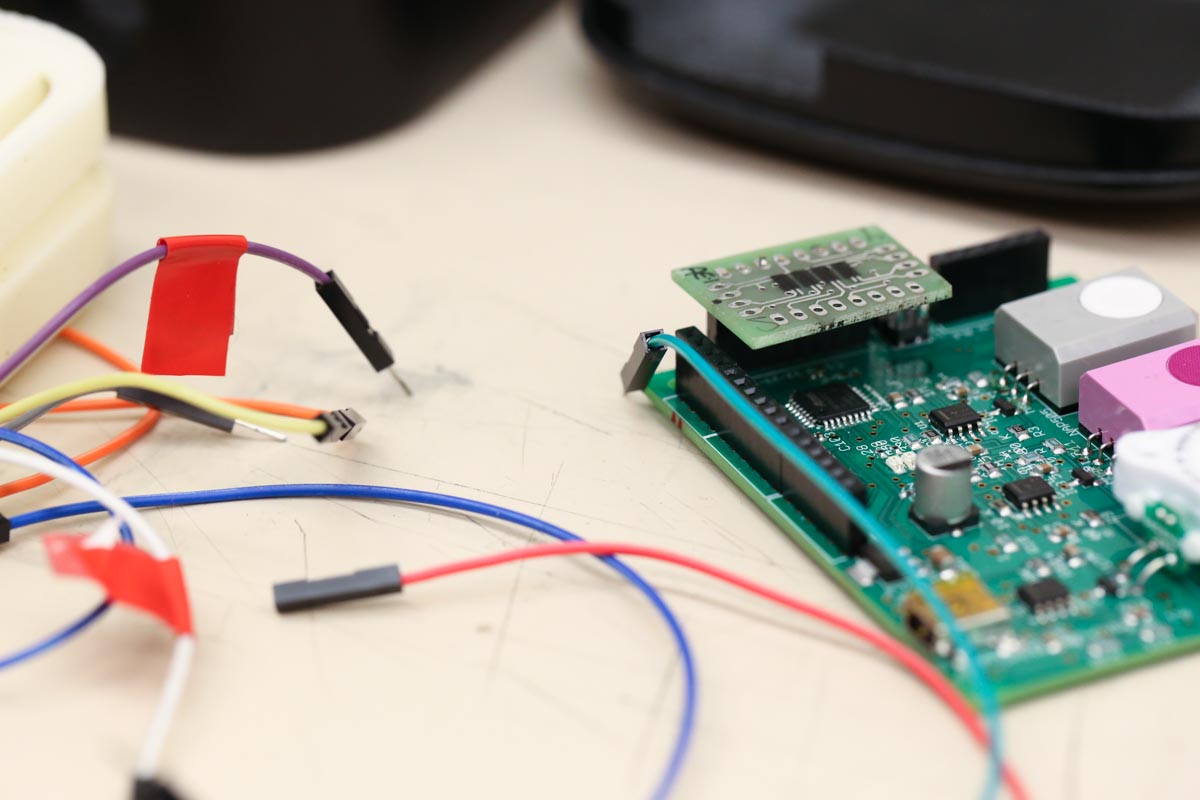

Will shares that the team did in fact start out focusing on a portable sensor that could be embedded in fabric or other materials. “Finding ways to incorporate the hardware into a wearable sensor is certainly a long-term focus for us,” he says, but explains that when they were in the process of iterating prototypes to get down to a smaller, wearable device, a number of companies approached ChemiSense saying, “Hey, we don’t want to wait. We want to embed the devices you guys have now into our products.”

“It really made sense for us as a brand new company to establish our foothold in the market with the devices that we already had.”

What was it about these intermediate prototypes that the companies found so attractive? See above: the detection scope. “There are so many different factors that go into air quality,” says Will, “and our devices detect them all—and are still much smaller than the traditional sensor.”

For companies dealing with everything from employee health and regulatory requirements to fugitive emissions and early leak detection, a full-scope air quality sensor is a dream come true.

Not to mention the sensors ChemiSense builds are also extremely low power—they run on less than a milliwatt.

Opportunity Knocks

When large customers come knocking, you don’t shut the door. To Will’s and Brian’s credit, instead of turning those companies away with a “come back when we’re done” note, they recognized the opportunity staring them in the face and immediately pivoted to take full advantage of it.

“It really made sense for us as a brand new company to establish our foothold in the market with the devices that we already had, and to turn them into viable products as quickly as possible for these customers, because there’s such a high demand for them,” says Will.

Customers are now asking for 500, 1500 devices at a time, and that requires scaling reliably and consistently.

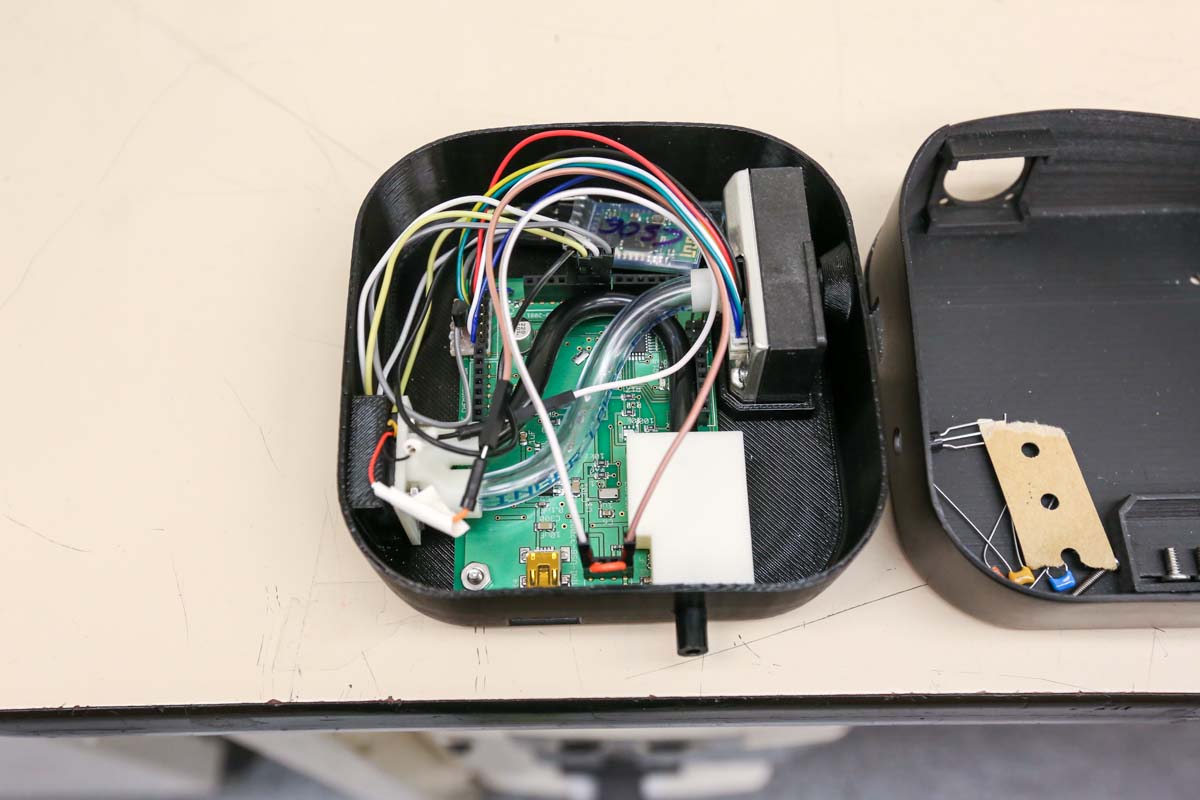

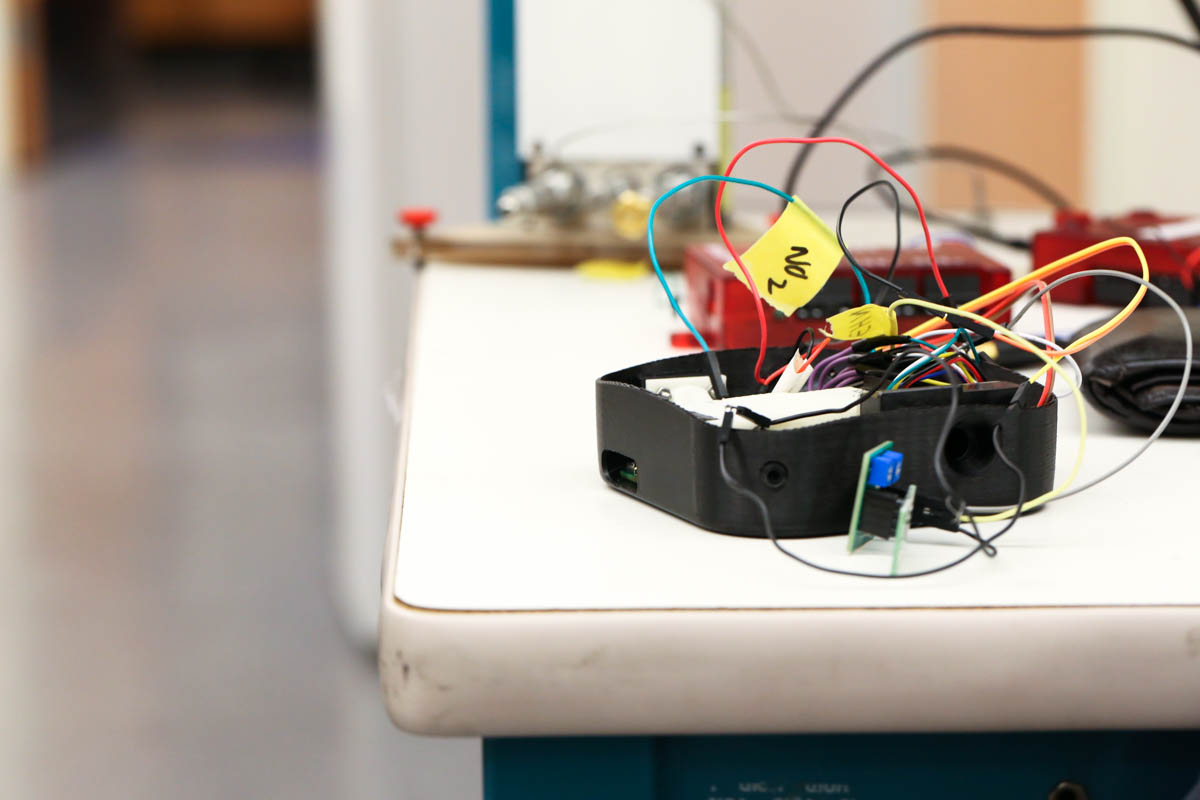

“This is why having the right tools is extremely valuable, and by that I mean firms like Fictiv or even your own 3D printers,” Will says. “We’ve seen a lot of great results from the prototypes that we’ve developed with Fictiv. We 3D print our outside casing, since we need constant air flow over the sensor, and the housing for the internal selectively permeable membranes that we use. Having manufacturing and design partners we can rely on to produce prototypes quickly and consistently is nothing short of business critical.”

Forget Location. It’s Lab, Lab, Lab.

Manufacturing physical products naturally requires physical facilities, but not all labs are created equal. Will and Brian were fortunate to be part of the broader University of California system, which offers great resources like the QB3 network, a series of private labs at universities throughout the Bay Area. For ChemiSense, a highly tech-focused company, QB3 was on their radar from the word go.

“We wanted to create an air quality sensor that not only works extremely well, but one people can actually afford.”

“You have to apply to get into the labs,” says Will, “but once you’re accepted, you maintain full IP ownership and you get to share a lot of the resources, like having a fume hood and access to profilometers. The fume hood sounds really simple but it’s key, absolutely key if you don’t want to be intoxicated by all the noxious gases your devices are supposed to be picking up.”

As for the profilometers, those are “very expensive” machines that can tell you how many atoms thick each polymer blend film is. “That’s extremely important for optimizing the performance of the sensors,” says Will.

The Multiple Roles Design Plays

From Apple to Stanford’s d.school, design permeates our world. It colors the way we think, the way we create products, and the way we relate to our society. Why should only clothes, shoes, and cars be fashionable and sexy? Why not environmental sensors, too?

“We wanted to create an air quality sensor that not only works extremely well, but one people can actually afford, enjoy interacting with,” says Will, “and benefit from in terms of comfort and health.”

Translated into design speak, this means turning the device inside out and re-inventing it from the ground up. Design weighs heavily in every aspect of ChemiSense’s approach, from the color, shape and materials of the casing to controlling for airflow and defining the precise path of analytes as they pass over the sensors, which is critical to improving their efficacy and performance.

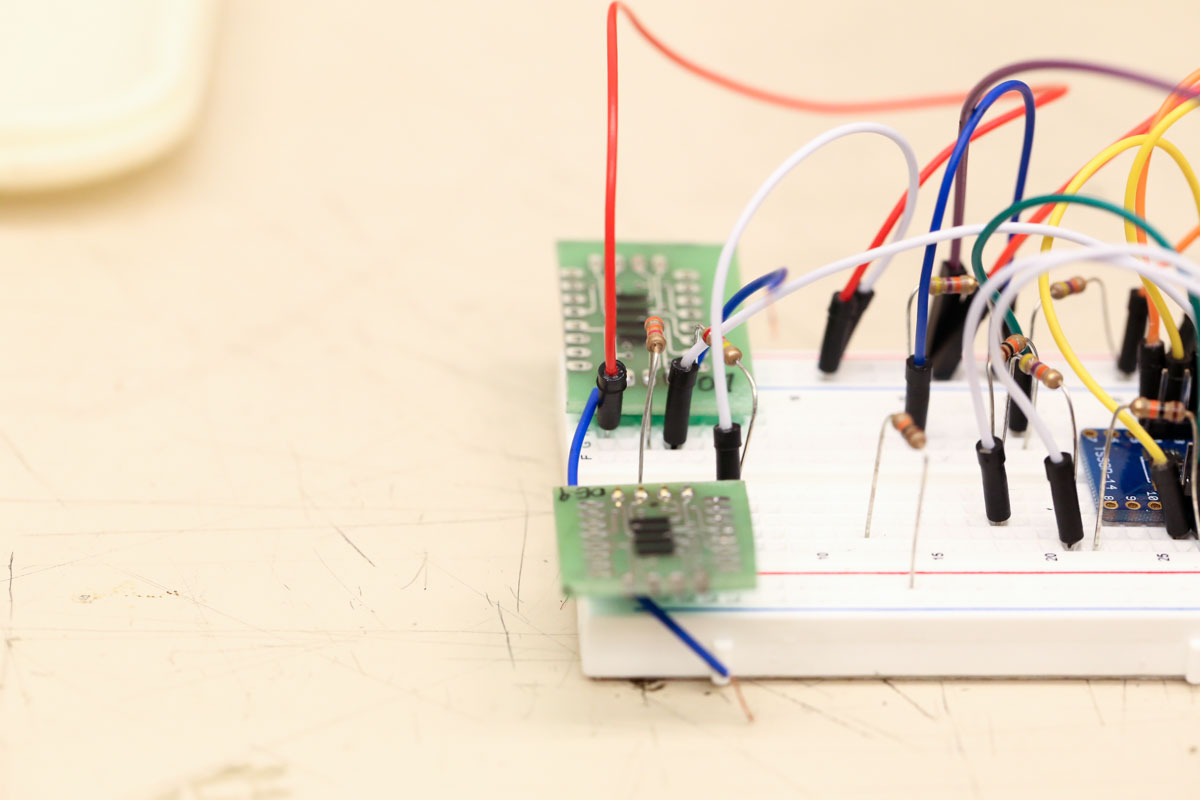

“The technology we use is polymer-based,” explains Will. “We use 20 or so different polymers, treat them with various conductive materials, and then optimize the ratios of these blends specifically for the chemical or element we are trying to detect. So we end up with a material that inherently detects the target elements, without needing to make the sensor microcombust to make it work.”

Yes, you heard that right: traditional air quality sensors have a microcombustion chamber that heats up to a balmy 300 degrees Celsius. You then measure how much of the air inside combusts, compare that to a baseline of non-combusting air, and analyze the differences in… you get the idea. Not simple. Not elegant. Not practical. Certainly not portable unless you’re wearing an Iron Man suit.

Optimize, optimize, optimize, adjust, adjust, adjust.

But ChemiSense goes further still: the sensors are placed into an array so that they can talk to each other. If one sensor reacts a certain way, ChemiSense’s proprietary algorithms can compare that reaction to the responses of all the other sensors on the array, as well as how they’ve historically responded. The entire device functions as one.

Just how did this simple yet sophisticated design come about? Confesses Will, “we actually took sort of a weird approach. We worked almost entirely on the hardware first before we got into software, and that was because the software end we had already all planned out.”

He pauses, and clarifies. The company developed their own prototyping process that involved an internal software model of how they thought things should behave, then used that model to work through all the hardware iterations and development. Once they were sure the hardware worked the way they wanted, they readjusted the entire model to make it more accurate for the next iteration. And only then did the team feel they were ready to wrap the software shell around the device.

“We kept pushing the sensitivity limits further and further with each iteration,” says Will. “Optimize, optimize, optimize, adjust, adjust, adjust. And we built in an automatic software calibration which…”—Will pauses, taking a breath for impact—“which we don’t know has actually been done before for environmental sensors. You cannot afford a false positive or a false negative. So you need to detect everything. You need to see ‘what everyone’s thinking.’ ”

Indeed. In a world awash with a veritable soup of pollutants, testing for one or two elements seems a bit antiquated.

Brave New Breathable World

Brian and Will’s passion for a smarter, simpler, more functional air quality sensor has already become material reality: they have redesigned the way it’s built, what and how much it detects, how it works, how it’s used and how much it costs. They are redirecting more than just air flow; they’re shifting the direction of an entire field.

“The metrics of environmental sensing don’t really change from sector to sector,” says Will, “or even between consumers and industry, so that’s a blessing in disguise for us because we can focus on creating the overall platform rather than just individual products.”

But the two are careful not to veer off the path of humility. For them, the big challenge that remains is how to maintain that star sensor performance and device-to-person relationship as they scale up to respond to what we all hope will turn into some serious industry and consumer demand.