Time to read: 6 min

If you’re developing a product, you’ve probably come across the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) approach, which seeks to create a product with the highest return on investment and the lowest risk. The idea was popularized in Eric Ries’ book The Lean Startup.

Ries focuses on software development for startups, but many of the principles can be adapted to developing a physical product. The idea of building prototypes, testing, learning, failing fast and early, and quickly iterating the next version is really nothing new. At Design Concepts, this is a process we have done for decades when developing a tangible product. New name… not a new idea.

Who Should Use an MVP for What?

An MVP, according to Ries, is “that version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort.”

Within the context of software development, The Lean Startup describes an MVP as a product that the consumer actually pays money for. Selling and shipping an actual product to a consumer validates key assumptions in a more concrete way than soliciting feedback based on a prototype. For the most part, this works for software, apps and websites where iteration is fast and there are no manufacturing costs. But can it work for a tangible consumer product? It depends on a few factors including whether:

- Selling the product requires infrastructure and distribution channels

- The product features cannot be independently evaluated

- The project requires market power to implement

- A product that is merely “viable” isn’t compelling enough to a consumer

- Showing the concept to the public requires a patent

- Showing the concept in a user interview requires an NDA (non-disclosure agreement)

If you answer “yes” to most of these questions, it is more likely that a full-featured product will produce more accurate feedback than an MVP.

For startups who may lack knowledge of their customers and the market, an MVP can be very useful. It can help prove the viability of a company’s business model to investors, estimate market size, define required product features and identify profitability on a per-customer basis. In addition, startups have the luxury of not needing to maintain the integrity of a brand, so all the learning you get from that less-than-amazing MVP won’t bite you later, when you launch the fully functional product.

On the other hand, for more established companies that know their customers’ desires, understand the market, and have shipped successful products, an MVP may carry more risks than reward.

MVP is also a useful approach for testing a disruptive product. The beauty of an MVP is in providing quick information in an uncertain situation. For new, untested and experimental concepts where the problem and solution are unknown, customers probably wouldn’t know which features to ask for—the market is unpredictable. So getting something simple in customers’ hands to try and provide feedback on the foundational idea can be extremely valuable.

Also note that highly regulated medical products and evolutionary products with a known problem and solution are poor candidates for an MVP.

5 Core Principles of MVP Development

Before you start down the path of developing an MVP, here are five core principles to keep in mind:

- Firm up your idea. Your concept should be clear and defined. If you can’t easily explain it, your customer won’t understand it.

- Define minimum viability for your product. What do you absolutely need to learn from customers? Design to this goal and stop there. Simplicity and speed is what MVP is all about.

- Build similar to intent. In the early phase of development, watching something fail can be more informative than success. For example, playing with scale and finish can yield useful feedback: Is big and shiny impressive, or does it read “too expensive”? You want to drive a reaction and build to learn.

- Iterate quickly. An important part of the process is to keep moving. Take the learnings from that first MVP, make improvements quickly, and get the next iteration out for further feedback. MVP is meant to speed development, not slow it down.

- Find the people with passion for what you’re doing. You don’t need a big sample size. You do, however, need to find opinionated early adopters or a small pool of people with deep knowledge about the area in which you’re ideating. One good person who can articulate what he likes is better than 10 know-nothings when you’re trying to iterate quickly.

Out-of-the-box MVP Approaches

There are also a variety of ways to prototype a product for quick learning and iteration that capture the spirit of MVP while respecting the realities of creating a tangible product:

- Visualize and share. Create a video of a visual model and a web page to gather data on clicks. Perhaps it’s supported with an online ad targeted to your user profile to draw people to the site. The learnings from how people interact with your web page can help you quickly redefine the feature set, refine your sales pitch, and learn about your customers.

- DIY. Appeal to early adopters by selling a “make-your-own” version through Kickstarter or another established channel. For example, Pensa Labs refined their sales pitch and feature set for the DI Wire bender by doing just that. It’s a relatively low-cost way to get a product out to those most interested in your solution and co-opt them to improve your design.

- Concierge MVP. Find your first customer and sell them a hand-built prototype specific to their needs. Get their feedback and sell them a refined prototype.

- Smoke test. This is an old, but useful, technique. Build the marketing materials and let customers pre-order the product before it has been built. The rub? It only works if customers are willing to try the product.

Metrics and Movement

The MVP model is all about getting the right information to propel development quickly and effectively. That means setting the right metrics. Ries advises against measuring “vanity metrics” such as the number of clicks on a website. Instead, measure customer flows through a website, conversions, purchases, number of pages viewed, etc. This is where the rich insights live.

Ries also recommends to always do split testing, offering two different versions of a product, advertisement or website where there is only one difference. Otherwise, it’s impossible to evaluate what caused variation in preference. Seeking a net promoter score (“How likely are you to recommend this to a friend?”) also provides valuable insight.

As you make your plan, the team should ask if the metrics are:

- Actionable: Will you be able to discern what caused the effect?

- Accessible: Is the metric stated in a way that everyone on the project understands?

- Auditable: Will you be able to spot-check the data by talking to customers?

Some of the MVP metrics that are applicable to the tangible products we typically design include the percentage of people:

- Interested in buying the product

- Willing to pay a particular price for it

- That will actually use it

- Who will tell their friends about it

To set the right metrics, identify the assumptions you need to validate and what decisions you expect to make before building a prototype, running a test or doing research. That may seem obvious, but it can get lost in the shuffle when great concepts have people excited and motivated to move first and think later.

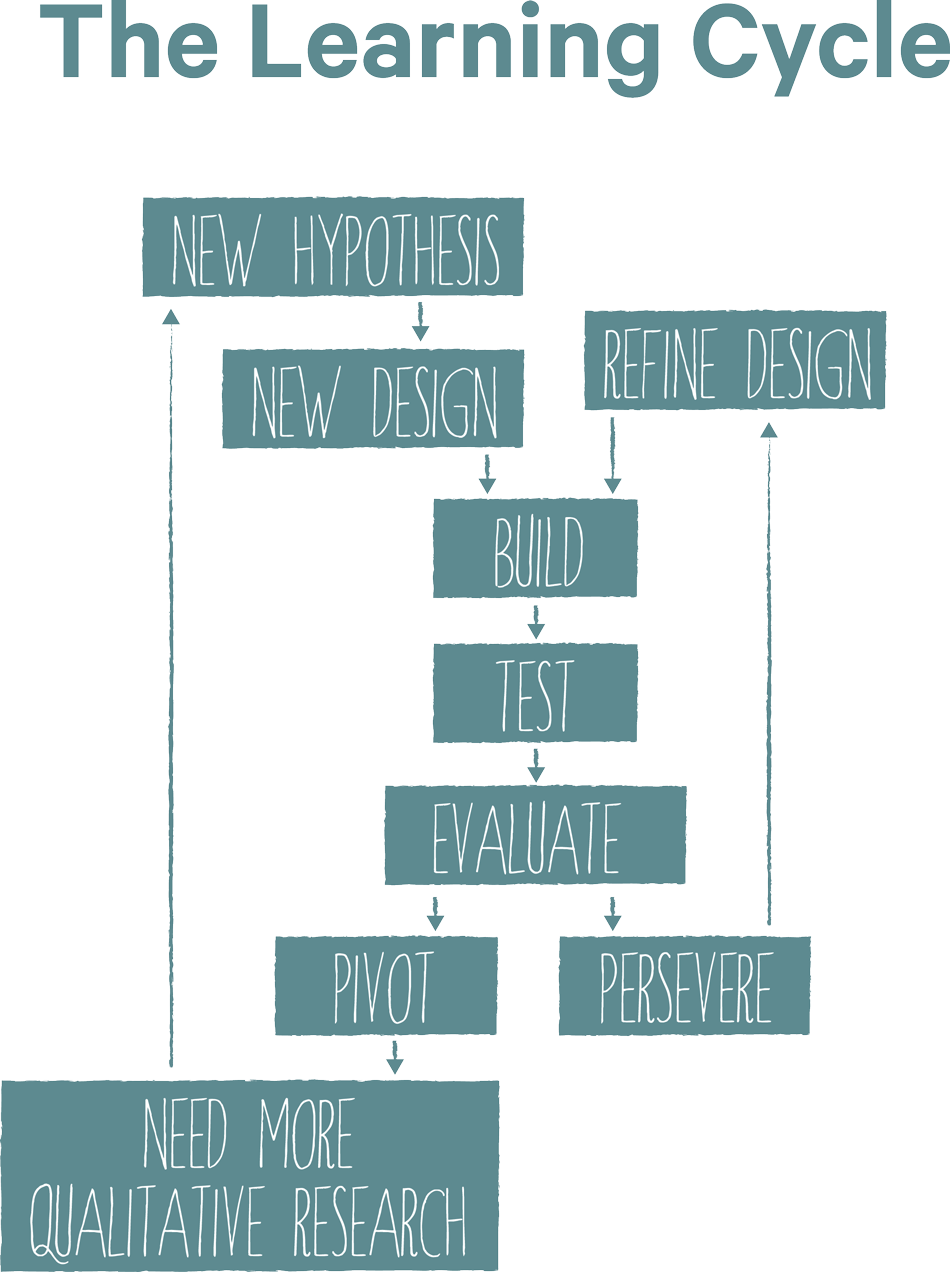

As fast of possible (within a month), go through a cycle that results in a set of quantifiable metrics that prove the growth model that is required for the business to succeed (or not). You only need to test the assumptions, differences or hypotheses that are new for this iteration of the product. It will likely take several versions until you hit upon the sweet spot, but by moving through quick iteration cycles, MVP helps you avoid analysis paralysis.

Is MVP Right for Your Project?

As product designers, we have been doing variations of the MVP process for years. When thoughtfully applied, many of these principles can help you create a faster feedback loop, provide quantifiable metrics, and ascertain effective customer communication strategies for your ultimate product launch.