Time to read: 8 min

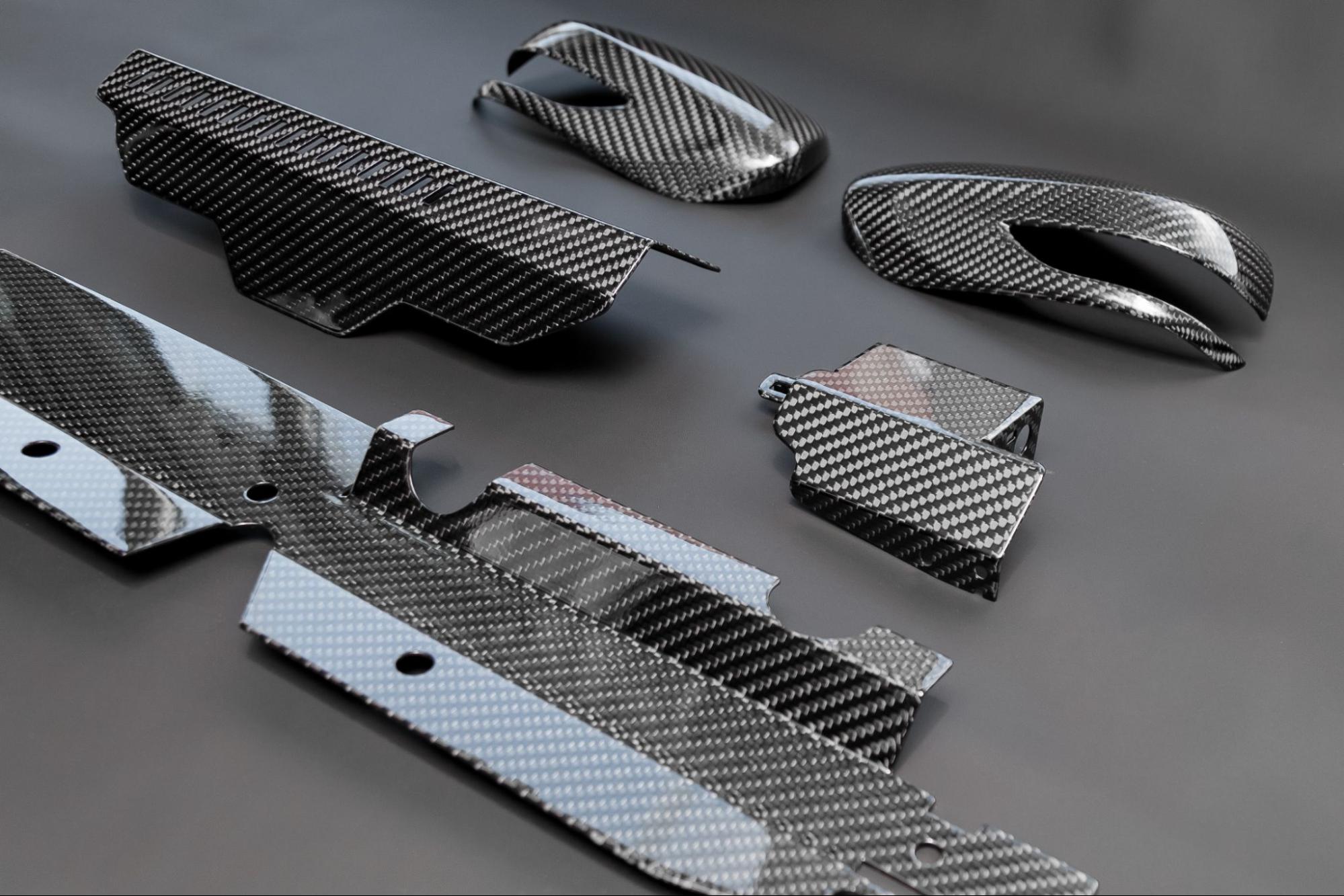

Composite layup is not a single manufacturing method—it’s a family of precise practices that transform fibers and resin into high-performance engineered materials. When fiber orientation, consolidation, and cure are executed according to Design for Manufacturability (DFM) principles, the result is a part with an exceptional strength-to-weight ratio.

This manufacturing approach underpins lightweight structural performance in aerospace, EVs, robotics, industrial equipment, and sports technology. You’ll find composite layups in products ranging from UAV airframes and aircraft structures to bicycle frames, pressure vessels, and protective equipment.

This article covers the composite layup process, key layup methods, materials, laminate architecture, defects and troubleshooting, and practical design guidelines for manufacturable, high-quality composites.

Why Composite Layup Matters

Engineering teams choose composite laminates because they allow load-path-specific reinforcement—something metals cannot provide without large mass penalties.

- Aerospace engineers cut kilograms, not grams.

- EV designers extend range through aggressive lightweighting.

- Robotics teams need high stiffness without added inertia that reduces control bandwidth.

These advantages do not come from material selection alone. They result from laminate construction using a controlled composite layup process, in which high-strength fibers are deliberately aligned with load paths and embedded in a resin matrix that efficiently distributes stress.

This is why laminated composite construction has become the standard manufacturing approach for aerospace skins, electric-vehicle body panels, wind turbine blades, and high-performance sporting components—from bicycle frames to racing shells and protective equipment.

What Is Composite Layup?

Composite layup is the process of placing sequential layers of fiber reinforcement—which are either dry or pre-impregnated with resin—onto a tool that defines the final geometry. Each ply is assigned a specific fiber orientation that determines stiffness, strength, and failure behavior.

A laminated composite structure is built from three fundamental structural elements:

- Reinforcement fibers (carbon, glass, or aramid) that carry tensile and flexural loads.

- The resin matrix (epoxy, polyester, or polyimide) that binds the fibers, transfers load between filaments, and sets the final shape after curing.

- A structural core (polymer, aluminum, or aramid honeycomb or foam) is used in sandwich panels to increase bending stiffness with minimal mass. The core is a permanent structural component used instead of adding additional fiber-resin layers when weight efficiency is critical.

Release films, peel plies, and vacuum bagging films are consumables that support processing but are not part of the finished laminate.

The Composite Layup Process

While specific composite manufacturing methods vary, all composite layup techniques share three fundamental process stages: layup, consolidation, and curing.

Final part quality is determined not by the presence of these stages alone, but by how tightly a small number of controllable parameters are managed within each stage. The most critical factors are outlined below:

Tool Surface Preparation

The mold or tool surface must be free of debris, moisture, and oil, and coated with a compatible release agent. The cleanliness and surface finish at the tool–laminate interface directly translate into the surface quality of the finished composite and influence demolding behavior.

Ply Cutting and Kitting

Plies are cut using CNC blade cutters, laser cutters, or waterjet systems, depending on material type. The controlling factor is preservation of fiber orientation and edge integrity. This is best achieved through sharp tooling, minimal thermal input, and stable fixturing to prevent fiber pull-out and distortion.

Ply Placement and Drape Control

A major factor during layup is conforming fibers to the tool without inducing wrinkles, bridging, or in-plane distortion. Bridging occurs when a ply spans a concave radius without fully contacting the tool; trapped air refers to local voids between layers. Both are avoided through proper ply sizing, sequential compaction, and controlled placement tension.

Consolidation Pressure and Air Removal

Vacuum bagging or external pressure is applied to evacuate trapped air, drive resin through the fiber bed, densify the laminate, and improve ply-to-ply adhesion. This step also governs bond quality to any core material and directly affects surface finish.

Cure Temperature and Time Control

Curing controls resin crosslink density, glass transition temperature (Tg), and final mechanical properties. Undercure reduces strength, while overcure can cause embrittlement and residual stress.

Controlled Cooling and Demolding

After cure, controlled cooling minimizes thermal gradients, residual stress, and spring-back, stabilizing final part geometry before release from the tool.

Composite Layup Methods

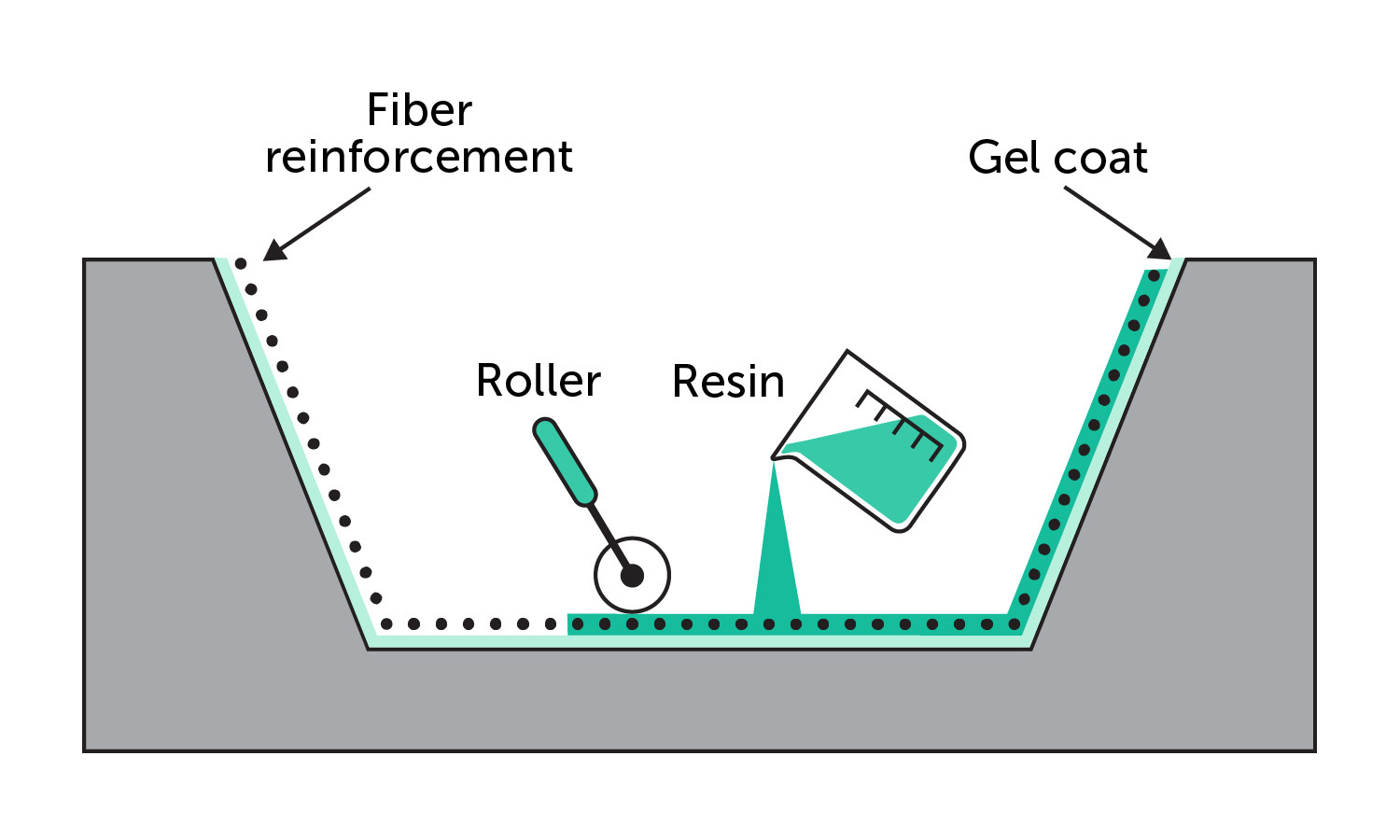

Hand Layup (Wet Layup)

In hand layup, dry fiberglass or carbon fiber fabric is placed onto the tool surface and manually impregnated with liquid resin, typically using rollers or brushes. This method is well-suited to large parts with relatively simple curvature and low structural loading, such as marine hulls, fairings, and industrial covers.

Its primary advantages are low tooling cost, minimal equipment requirements, and flexibility for prototyping and short runs.

Limitations arise from operator-to-operator variability, difficulty controlling fiber volume fraction, higher void content, and slow production rates.

Prepreg Layup

Prepreg materials are fiber reinforcements pre-impregnated with a precisely metered resin-to-fiber ratio. Because the resin is partially cured to a B-stage, prepreg must be stored frozen to slow the curing reaction and preserve shelf life, which is often only days at room temperature.

Plies are laid dry onto the tool, consolidated under vacuum, and cured in large industrial ovens or autoclaves, some of which are big enough to hold entire aircraft fuselage sections or wing skins.

This method delivers excellent control of mechanical properties, low void content, and a clean working environment with minimal exposure to liquid resins and solvents.

The trade-offs are high material costs, cold-storage logistics, and strict temperature control during curing.

Resin Infusion (Vacuum-Assisted Resin Transfer Molding, VARTM)

In resin infusion, dry fiber preforms are placed on the tool, sealed under a vacuum bag, and liquid resin is drawn through the laminate by vacuum pressure. This method is widely used for large structures such as wind turbine blades and automotive body panels, where prepreg costs are prohibitive.

Flow behavior is the governing risk. Poor gate and vent design can cause uneven wet-out, producing resin-rich or resin-starved regions.

Automated Fiber Placement (AFP)

AFP uses robotic systems to place narrow fiber bundles (tows) or tapes along programmed paths. It enables precise fiber steering, low scrap rates, and highly repeatable production of complex curved shells.

AFP is used for aerospace structures produced in moderate series volumes, where dimensional repeatability justifies the investment.

The main barriers are the very high capital cost and the need for specialized programming and process expertise.

Fiber Orientation and Laminate Architecture

Fiber orientation controls how a laminate carries load. A laminate with all fibers oriented in the same direction (0°) resists tensile forces along the fiber axis, but has poor strength transverse to the fibers and is susceptible to shear-driven buckling.

A ±45° fiber pair, meaning two plies oriented at +45° and −45° relative to the load axis (forming an “X” pattern), resists in-plane shear and torsional loads.

Plies oriented at 90° resist transverse tension and bending by carrying load across the primary fiber direction.

When these orientations are combined into a balanced stacking sequence such as [0 / ±45 / 90], the laminate exhibits multidirectional, near-isotropic in-plane stiffness with high strength-to-weight efficiency.

Relationship Between Fiber Orientation and Stress Modes Resisted

| Fiber Orientation | Primary Stress Modes Resisted | Typical Applications |

| 0° | Axial tension and compression | Monocoques, spars, bike frames |

| ±45° | Shear and torsion | Enclosures, structural skins of vehicles |

| 90° | Transverse tension and bending | Cross members, fairings |

| Quasi-isotropic | Multidirectional in-plane loading | Aerospace skins, EV panels |

Fiber orientations are not fixed patterns. The stacking sequence is selected based on load paths, boundary conditions, and stiffness targets and can vary significantly across components within the same structure.

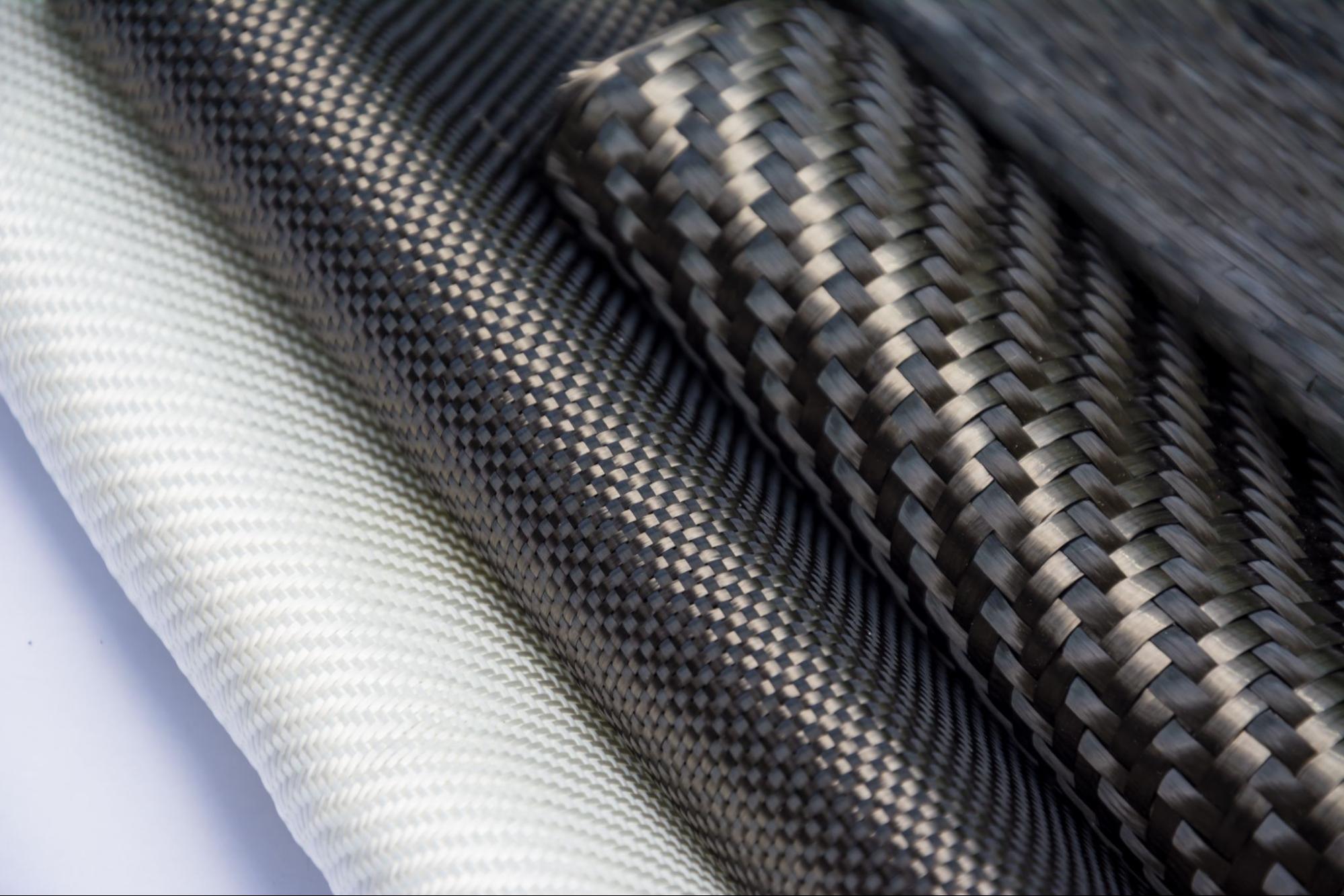

Materials for Composite Laminates

Composite laminates combine a reinforcement fiber with a polymer matrix. The fiber provides stiffness and strength, while the matrix transfers load between fibers, protects them from damage, and defines thermal and chemical limits. Standard fiber-matrix systems are:

- Carbon fiber with an epoxy matrix: The most common system for high-stiffness-to-weight aerospace, automotive, and robotics structures.

- Glass fiber with a polyester or vinyl ester resin matrix: Widely used where cost, corrosion resistance, and fatigue durability are prioritized over maximum stiffness.

- Aramid (Kevlar) fiber with epoxy matrix: Provides exceptional impact and energy absorption, which is why it is used in ballistic and protective applications.

- Carbon fiber with thermoplastic matrices such as PEEK or PEKK: Enables weldability, recyclability, and high-temperature performance for demanding aerospace and medical uses.

- Hybrid laminates (combine glass and carbon fibers in a single part): Balances cost, stiffness, and damage tolerance.

Common Defects and Troubleshooting for Composites

Most defects in laminate manufacturing stem from trapped air, uneven pressure, or misaligned fibers. The table below summarizes typical issues, their causes, and corrective actions.

Common Composite Layup Defects

| Defect | Cause | Prevention / Mitigation |

| Delamination | Poor bonding between plies due to insufficient consolidation or curing | Apply consistent vacuum/pressure; follow precise cure schedule |

| Voids | Incomplete air evacuation or insufficient compaction | Verify vacuum bag integrity; ensure vacuum level and dwell time are adequate |

| Wrinkles | Fiber buckling during placement or draping over complex contours | Use appropriately cut ply sizes (matching geometry) and maintain fiber tension |

| Resin-rich zones | Local excess resin or fiber defects (holes, gaps) | Check fiber integrity before layup; control resin content; consider prepreg for consistent resin ratio |

| Fiber shifting | Fibers move during resin infusion or compaction | Reduce resin viscosity; secure fibers; select proper fabric type and orientation |

Composite Design for Manufacturability (DFM) Guidelines

Successful composite fabrication requires designing buildable structures rather than purely idealized models. A laminate may meet finite element analysis (FEA) predictions but still fail to be manufactured if plies cannot drape properly over complex features or corners that create fiber fracture points. Key practical guidance for composites includes:

- Corner radii ≥ 3X ply thickness: Reduces fiber bridging and tearing during layup.

- Thickness tolerance ≤ 15% per region: Ensures structural consistency and avoids weak points.

- Balanced stacking across all layers: Not just ±45° plies, to prevent torsional or bending bias.

- Plan trimming and edge sealing early: Ensures proper fiber alignment and prevents resin wicking into exposed edges, which is harder to correct later.

Composite Layup FAQs

What is the composite layup process?

Composite layup is the manufacturing process of placing sequential layers of fiber reinforcement—either dry or resin-impregnated—onto a tool surface, followed by consolidation and curing. The process controls fiber orientation, resin distribution, and laminate thickness to achieve targeted mechanical performance.

What materials are used in composite layup?

Composite layup typically uses reinforcement fibers such as carbon fiber, fiberglass, or aramid, combined with a polymer resin matrix such as epoxy, polyester, or high-temperature thermoplastics. Core materials, including foam or honeycomb, may be added to increase bending stiffness without significantly increasing weight.

What’s the difference between hand layup and prepreg layup?

Hand layup involves manually wetting dry fiber fabrics with liquid resin, while prepreg layup uses fibers pre-impregnated with a controlled resin content. Prepreg layup provides higher fiber volume fraction, lower void content, and more consistent mechanical properties, but requires cold storage and controlled curing.

How does vacuum bagging improve composite quality?

Vacuum bagging removes trapped air, compacts laminate layers, and promotes uniform resin distribution during cure. By applying consistent pressure across the laminate, vacuum bagging reduces void content, improves fiber-to-resin bonding, and enhances surface finish and mechanical performance.

What are common defects in composite layup?

Common composite layup defects include voids, delamination, wrinkles, resin-rich zones, and fiber misalignment. These issues are typically caused by inadequate consolidation pressure, poor drape control, improper resin flow, or incorrect cure cycles. They can be mitigated through proper tooling, vacuum integrity, and process control.

Strong Composites Begin at Layup

Achieving high-performance composites requires a disciplined and controlled approach at every step of the layup process. By rigorously managing fiber orientation, consolidation, and curing, manufacturers can eliminate common defects and unlock the full structural potential of fiber-reinforced laminates. The goal is not just a manufactured part, but an engineered material.

If you are designing a composite component and need support, Fictiv provides the infrastructure to move from laminate design to a physical part quickly.

Contact our team to get started on your manufacturing project.