Time to read: 12 min

When designing a product, much of the early focus naturally goes into the individual parts—what materials to use, how they’ll be manufactured, and whether each component can be made reliably. That work is critical, but it’s only part of the picture.

What’s often overlooked is how those parts come together into a complete, buildable unit. Assembly is where design intent meets manufacturing reality. It’s where tolerances stack up, where small design choices start to affect cycle time and labor cost, and where products either scale smoothly or become difficult and expensive to build.

Designing parts well is important. Designing how those parts assemble is what makes a product truly manufacturable.

For engineering teams under pressure to deliver faster and at lower cost, assembly design is one of the highest-leverage opportunities for improvement. Decisions made during early design—how parts locate, how they join, and how variation is absorbed—often determine whether a product scales smoothly or struggles in production.

In many real-life development programs, assembly costs exceed part fabrication costs, especially as production volumes scale. Every additional fastener, fixture, tolerance, or manual operation compounds cost, risk, and lead time.

Assembly is key to product quality, cost reduction, production speed, serviceability, and the customer experience.

This guide is a comprehensive, DFMA-driven resource for product assembly design, combining best practices in mechanical fastening, snap-fits, press-fits, adhesives, ultrasonic welding, heat staking, and sheet-metal welding.

Whether you are designing consumer electronics, industrial equipment, or complex electromechanical systems, this guide will help you make earlier, smarter assembly decisions that reduce costs, improve reliability, and accelerate time-to-market.

Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA)

What is DFMA?

Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA) is the practice of designing products to be easy to manufacture and assemble. While Design for Manufacturing (DFM) focuses on how individual parts are made, Design for Assembly (DFA) focuses on how those parts come together into a complete product.

From an assembly standpoint, DFMA prioritizes:

- Reducing part count

- Simplifying assembly steps

- Minimizing handling and orientation changes

- Lowering tolerance sensitivity

- Increasing repeatability and robustness

Assembly inefficiencies scale directly with volume. A design that is acceptable for a 20-unit pilot build can become cost-prohibitive at 10,000 units if assembly effort has not been optimized.

Why Assembly Drives Cost More Than You Expect

Assembly cost is influenced by factors beyond labor rates alone. Key cost drivers include:

- Number of assembly operations

- Time per operation

- Required skill level

- Tooling and fixturing complexity

- Rework, scrap, and quality escapes

Each additional part increases handling, inspection, and inventory complexity. Each additional fastener adds installation time, tool access constraints, and risk of human error. Choosing the wrong assembly method can also increase scrap rate, further driving up costs. DFMA aims to systematically eliminate these inefficiencies before they appear on the shop floor.

Core DFA Principles

Design for Assembly (DFA) is the practice of structuring parts and joints so products come together efficiently, cost‑effectively, and with minimal production risk.

The following principles form the foundation of effective assembly design:

- Minimize part count

Every part introduces cost, procurement overhead, and a potential failure mode. Question whether each part truly needs to exist. - Integrate functions where possible

A single molded or machined feature can often replace multiple discrete components, such as brackets, spacers, or alignment pins. - Design parts to be self-locating and self-fixturing

Tabs, slots, chamfers, and lead-ins reduce reliance on fixtures and manual alignment during assembly. - Eliminate unnecessary fasteners

Screws and bolts are useful but costly. Where loads and serviceability allow, replace fasteners with geometry. - Design for one-direction assembly

Gravity-assisted, top-down assembly is faster, safer, and more repeatable. - Prevent incorrect assembly (poka-yoke)

Asymmetric geometry ensures parts can only be assembled in the correct orientation. - Control tolerance stack-up early</br>Many assembly failures originate from tolerances that were never evaluated together.

DFMA as a Cross-Functional Tool

DFMA is most effective when applied collaboratively. Design engineers, manufacturing engineers, quality teams, and suppliers each see different risks. Reviewing assembly early—before drawings are frozen—prevents costly, disruptive late-stage redesigns.

Assembly Strategy and Joining Methods

One of the most common mistakes in product development is choosing a joining method too early. Screws, snap‑fits, adhesives, and welds are solutions—not strategies.

Before selecting a joining method, define what each joint must accomplish.

Define Joint Requirements

For every interface, document:

- Is the joint permanent or serviceable?

- What loads does it carry (tension, shear, peel)?

- Is alignment critical?

- What environmental exposure exists (temperature, moisture, chemicals)?

- What cosmetic requirements apply?

- What is the expected production volume?

Once these requirements are clear, the correct joining method often becomes much easier to identify.

Choosing the right joining method (a practical decision matrix)

Many assemblies mix joint types. The trick is assigning each joint a “job” (serviceability, strength, speed, sealing, cosmetics) and choosing accordingly.

Assembly Method Selection Table

The “Joint Strategy” That Scales

A production-friendly assembly often uses:

- Self-location features (tabs/slots/pins)

- One primary retention method (snap-fit, screws, weld, or adhesive)

- A secondary method only where needed (e.g., screws only at high-load points)

Engineering Fits and Tolerances for Assembly

Why Fits Matter

Engineering fits and tolerances play a foundational role in how an assembly comes together. They directly influence how much force is required to assemble parts, how quickly operators can complete each step, and how consistently parts align without rework or adjustment. Even small differences in fit can change an assembly from a smooth, repeatable process into one that requires excessive force, specialized tooling, or manual correction.

Beyond assembly effort, fit selection affects functional performance and long-term reliability. Parts that are too loose may vibrate, wear prematurely, or fail to meet alignment requirements. Parts that are too tight can crack, deform, or accumulate stress that leads to failure over time. Poor fit choices also increase scrap rates when natural manufacturing variation pushes parts outside of acceptable limits.

In practice, many assembly problems are not caused by a single incorrect dimension, but by fit decisions that did not account for variation, material behavior, or the realities of production-scale assembly.

Fits and tolerances determine:

- Assembly force and speed

- Alignment accuracy

- Functional performance

- Scrap rates

- Long‑term reliability

A poor fit choice can turn a simple assembly into a high‑variation process.

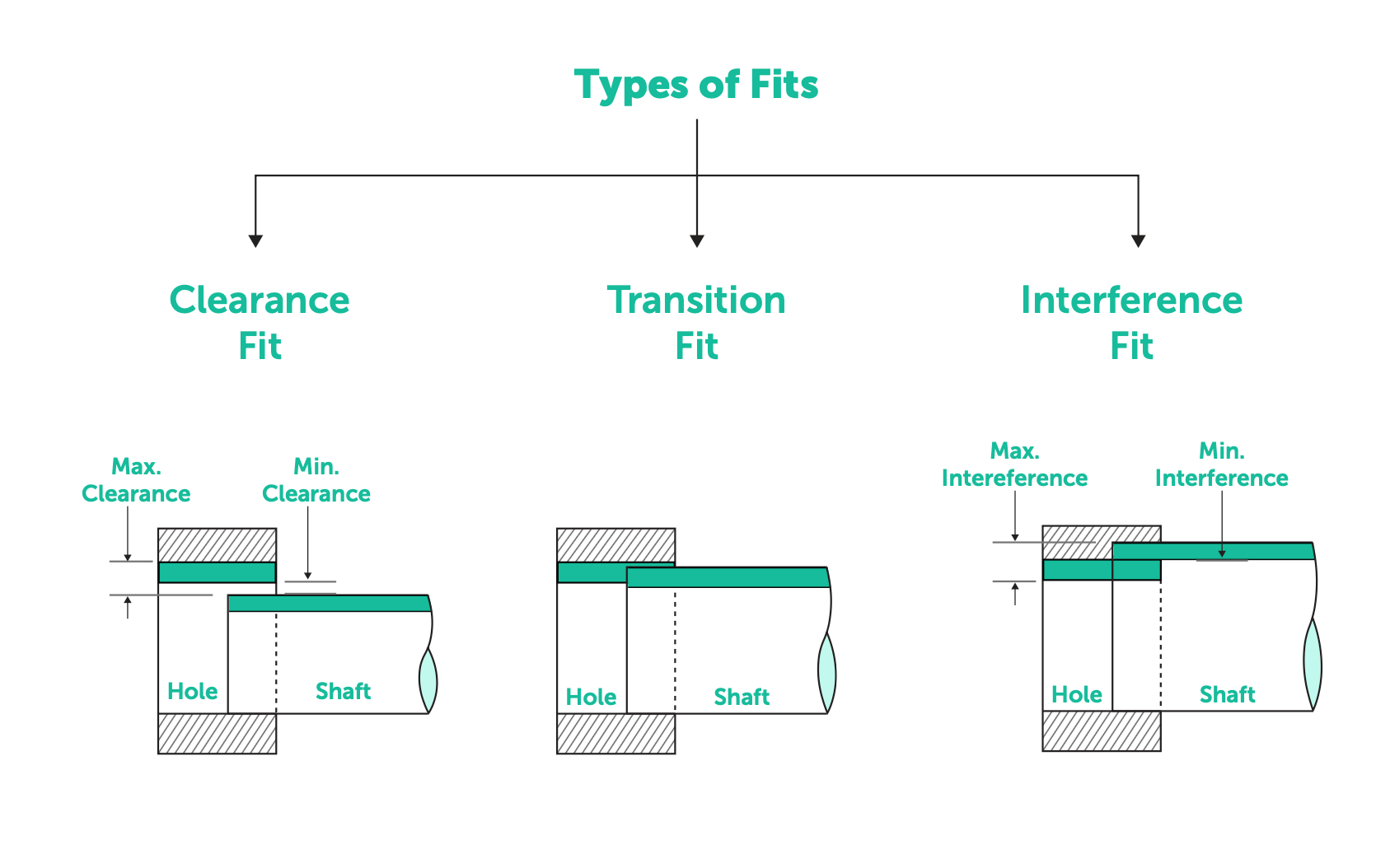

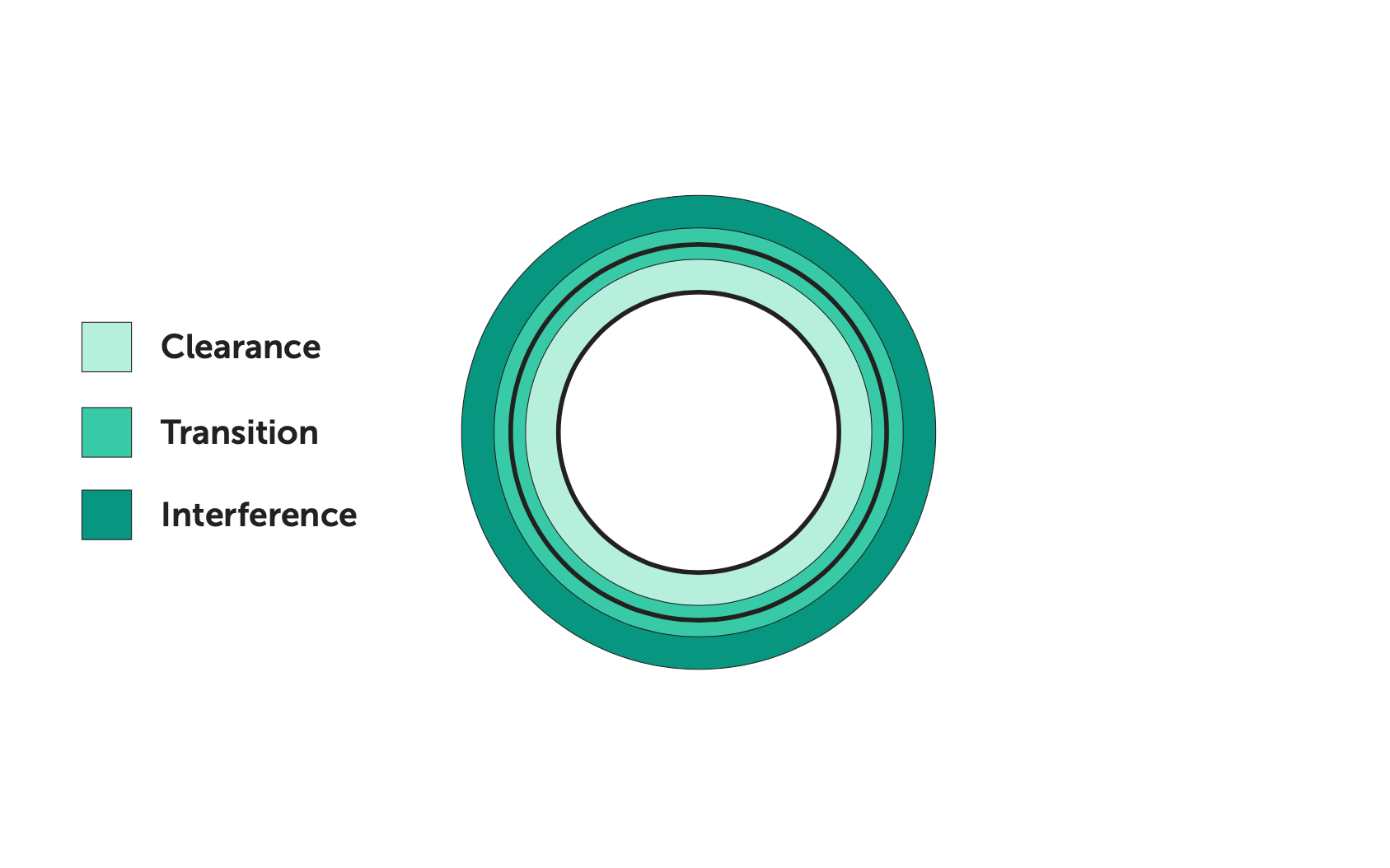

The Three Primary Fit Types

Clearance Fits

Clearance fits are designed so that the hole is always larger than the mating shaft, ensuring that parts assemble easily with minimal force. This type of fit allows relative motion between components and is the most forgiving option when it comes to manufacturing variation. Because clearance fits tolerate dimensional variation well, they are often preferred for high-volume production and manual assembly operations.

Common applications include rotating shafts, sliding mechanisms, removable covers, and non-critical alignment features. When ease of assembly, serviceability, or movement is required, clearance fits are typically the safest and most economical choice.

Clearance:

- Hole is always larger than the shaft

- Allows easy assembly and relative motion

- Most forgiving for variation

Common uses include rotating shafts, sliding components, and non‑critical alignment features.

Transition Fits

Transition fits fall between clearance and interference fits and may result in either a small clearance or a slight interference, depending on actual part dimensions. They are used when controlled alignment is required, but permanent retention is not. For example, transition fits can help align mating components during assembly while still allowing disassembly if needed.

Because transition fits sit on the edge of interference, they are more sensitive to tolerance variation than clearance fits. Small shifts in process capability can change how the parts assemble, so these fits should be used intentionally and validated with real manufacturing data rather than nominal dimensions alone.

Transition:

- Can result in either slight clearance or slight interference

- Used when controlled alignment is needed without permanent retention

Transition fits are sensitive to tolerance variation and should be used intentionally.

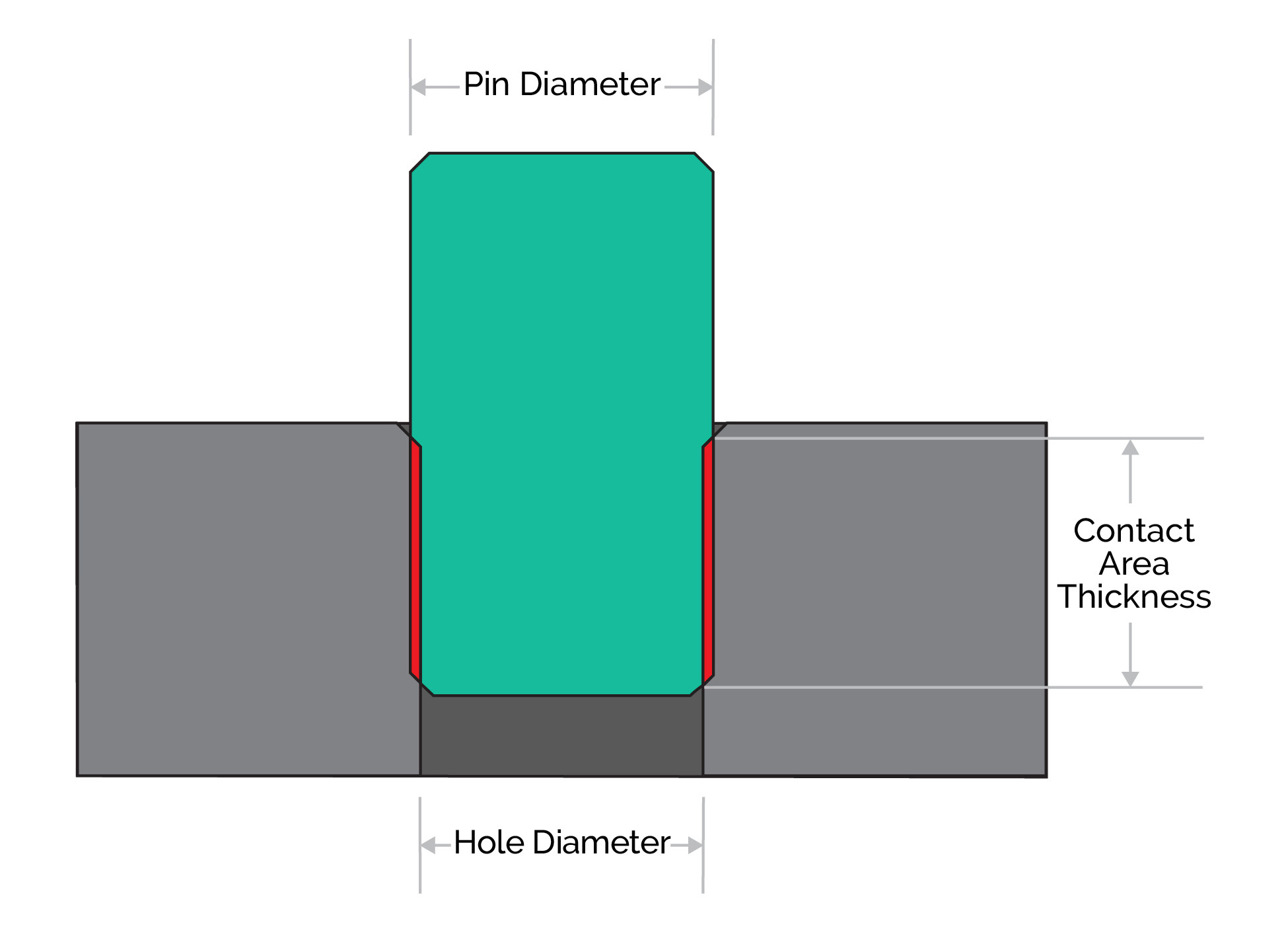

Interference (Press) Fits

Interference fits are designed so that the shaft is intentionally larger than the hole, creating retention through friction once the parts are assembled. These fits require force, thermal assistance, or both to assemble and produce joints that resist movement, vibration, and shear loads.

While interference fits can be highly effective, they are also unforgiving. Excessive interference can crack brittle materials or distort thin-walled components, while insufficient interference can eliminate retention entirely. Successful interference-fit design requires careful control of tolerances, material properties, and assembly methods.

Interference:

- Shaft is intentionally larger than the hole

- Requires force or thermal assistance

- Produces high friction and retention

Interference fits are powerful but unforgiving if not designed correctly.

Tolerance Stack‑Up

Many assembly failures occur not because a single dimension is out of tolerance, but because multiple tolerances accumulate in an unexpected way. This phenomenon, known as tolerance stack-up, can lead to misalignment, excessive stress, or parts that simply will not assemble.

To manage tolerance stack-up effectively, tight tolerances should only be applied where function truly demands them. Over-tolerancing drives cost without improving performance. Designers should also use datums intentionally to control alignment and avoid chaining tolerances across multiple parts whenever possible. Evaluating tolerance stack-up early—before prototypes or tooling are finalized—can prevent costly redesigns later in the program.

How to Reduce Stack-Up Risk:

- Tight tolerances should only exist where function demands them

- Use datums intentionally to control alignment

- Avoid chaining tolerances across multiple parts

- Let geometry handle location before relying on fit

Press (Interference) Fits

When to Use Press Fits

Press fits are well-suited for applications requiring high positional accuracy, compact joints, and resistance to shear and vibration without additional hardware. Because they rely on friction rather than fasteners, press fits can reduce part count and enable clean, space-efficient designs.

Typical applications include dowel pins for alignment, bearing installation, and shaft-to-hub connections. In these cases, the press fit provides both location and retention in a single operation.

Design Risks

Press fits introduce several risks:

- Small tolerance changes can eliminate interference

- Excessive interference can crack materials

- Thermal expansion mismatch can loosen or overstress joints

Best Practices for Press Fits:

- Avoid more than two press‑fit features per assembly operation

- Combine one press fit with one slip‑fit locator when alignment is required

- Validate with real manufacturing process capability

- Consider service temperature range and effects carefully

Download our Press Fit Calculator.

Snap‑Fit Design for Fast Assembly

Why Snap‑Fits Can Be a Great Option

Snap-fits replace traditional fasteners with integrated part geometry, allowing components to lock together during assembly without tools or additional hardware. This enables rapid assembly, reduces part count, and lowers overall bill-of-materials cost. Snap-fit assemblies also support clean external aesthetics, which is why they are widely used in consumer products, enclosures, and internal subassemblies.

When designed correctly, snap-fits can dramatically reduce assembly time and simplify logistics, making them especially attractive for high-volume production.

Snap‑fits replace fasteners with part geometry, enabling:

- Rapid, tool‑less assembly

- Lower part count

- Reduced BOM cost

- Clean aesthetics

Snap‑Fit Types

- Cantilever snap‑fits

- Annular snap‑fits

- Torsional snap‑fits

Each type has different stress behavior and retention characteristics.

Material Considerations

Snap‑fits rely on elastic deformation. Key considerations:

- Allowable strain of the material

- Long‑term creep behavior

- Manufacturing process (injection molding vs. 3D printing)

Tough, ductile thermoplastics generally perform best.

Design Tips:

- Add generous radii at the snap root

- Control deflection length to reduce strain

- Provide lead‑in chamfers for assembly

- Design for disassembly if required

- Plan for fixtures to help guide assembly

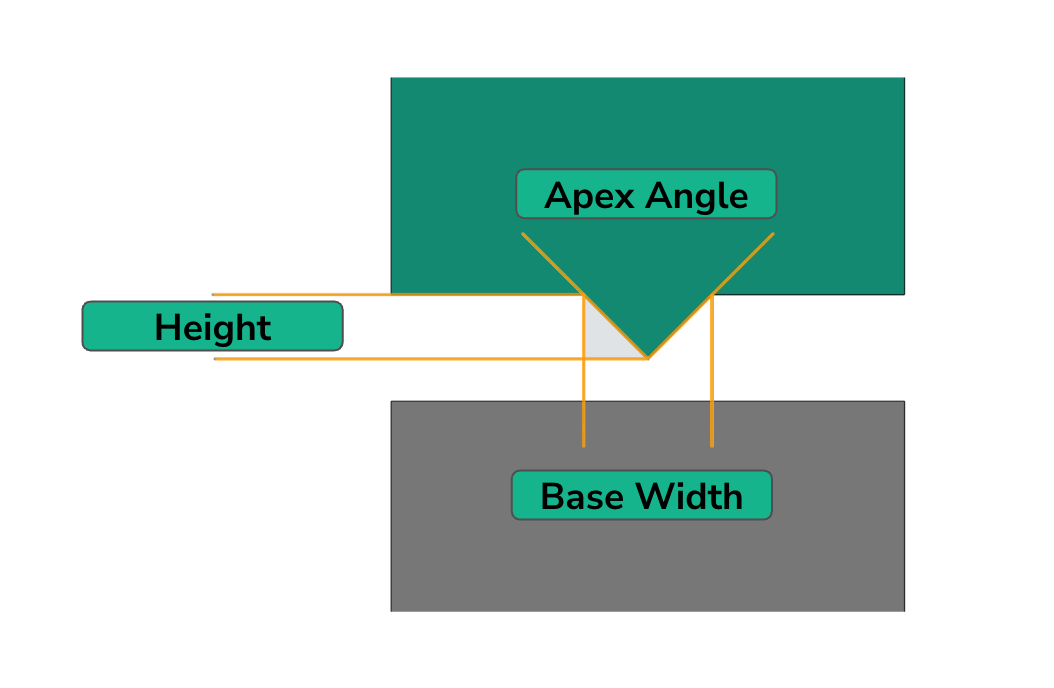

Ultrasonic Welding

How Ultrasonic Welding Works

Ultrasonic welding uses high-frequency vibration and pressure to melt thermoplastics at a joint interface. Once vibration stops, the molten material solidifies, creating a strong, repeatable bond in a matter of seconds

Advantages

- Very fast cycle times

- No consumables

- Strong, sealed joints

- High repeatability

Limitations

- Part size constraints

- Equipment, initial tooling, and process development

- Cosmetic flash if not designed correctly

Design Requirements:

- Energy directors or shear joints

- Consistent part geometry

- Controlled weld collapse

Assembly techniques like ultrasonic welding can be very effective, but also finicky. It’s critical to have a manufacturing partner that knows what they are doing and can dial in the process.

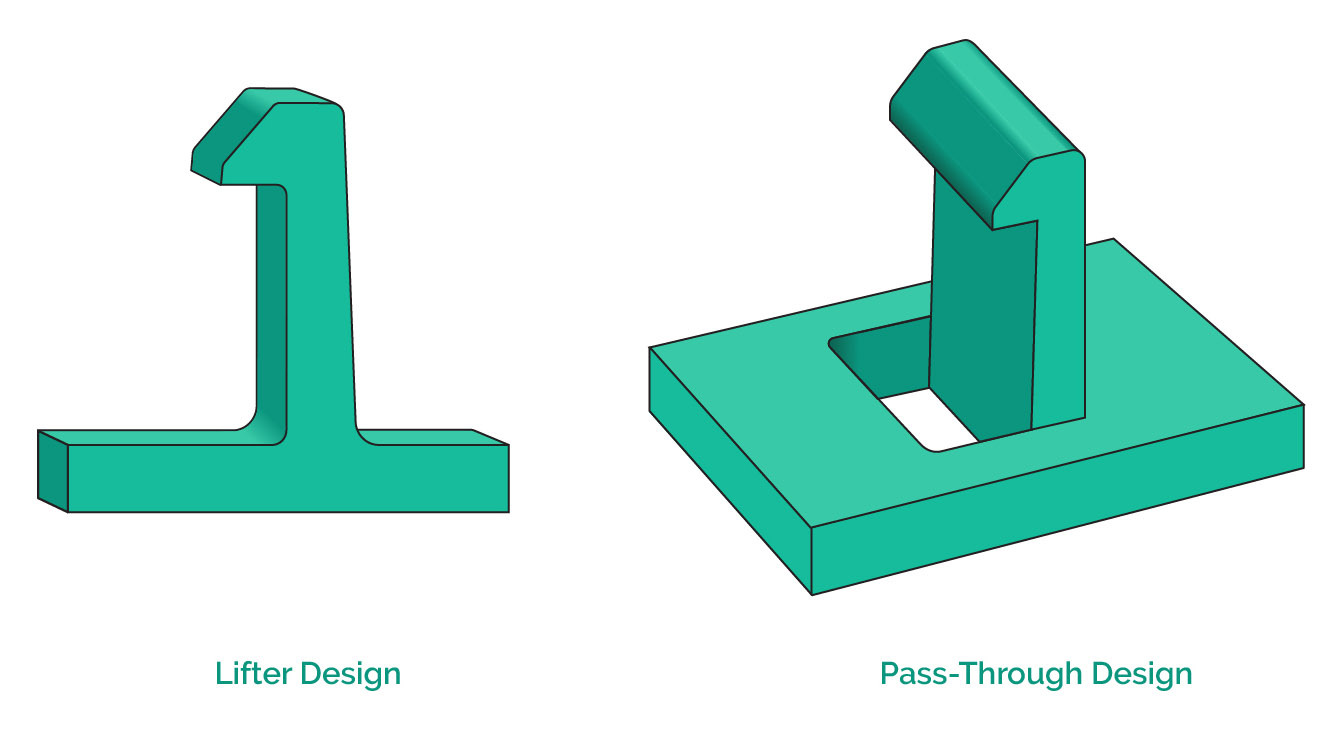

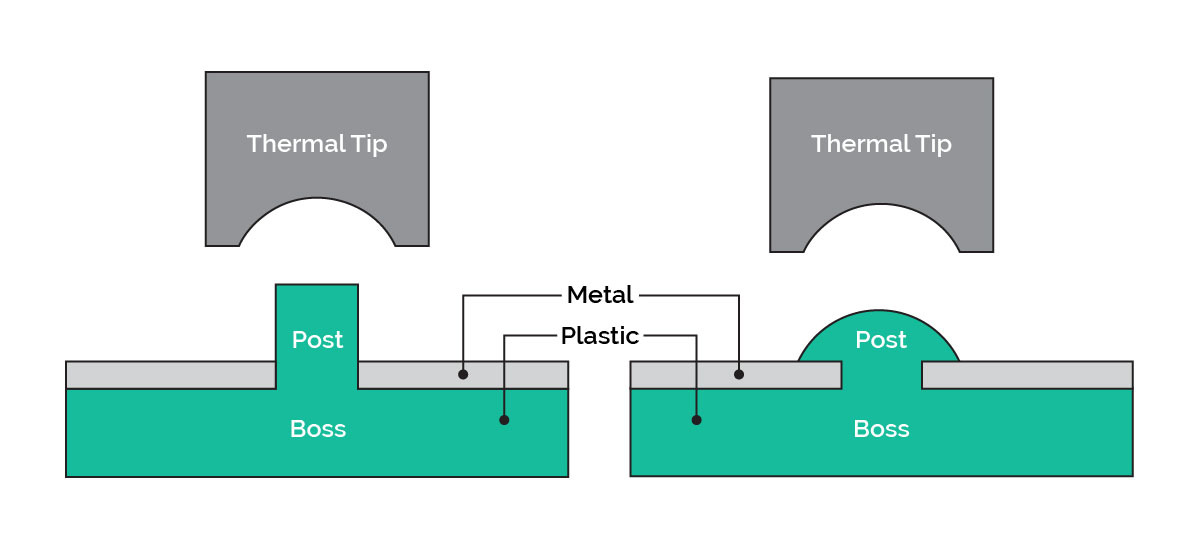

Heat Staking

What Is Heat Staking?

Heat staking reshapes thermoplastic bosses using controlled heat and pressure to mechanically lock another component in place. Rather than melting an interface, the plastic deforms to create a retaining head.

Common Applications

- Capturing PCBs

- Plastic‑to‑metal joints

- Installing threaded inserts

Pros and Cons

Pros:

- No added hardware

- Reliable retention

Cons:

- Slower cycle time than ultrasonic welding

- Permanent joints

- Visible stake heads

Sheet Metal Welding and Weldment Design

Welding in Assembly

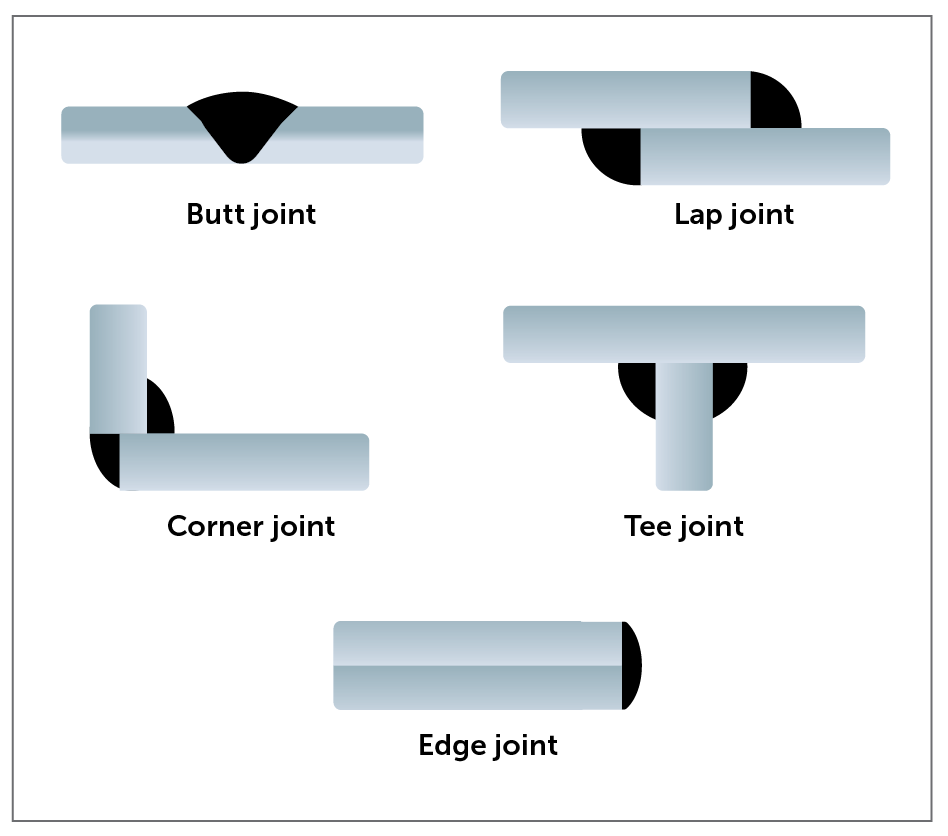

Sheet metal welding is used when high structural integrity and permanent joints are required. Because welding introduces heat and distortion, assembly-friendly weldment design is critical.

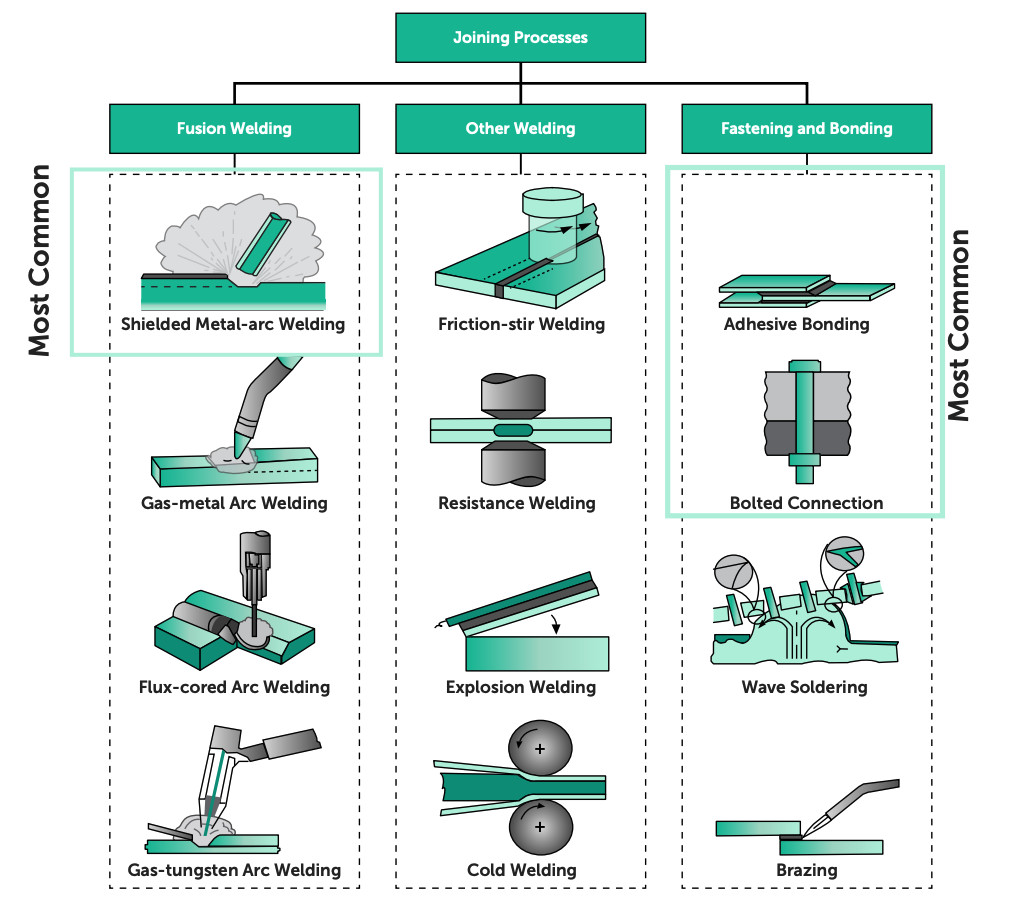

There are many ways to assemble metals, as pictured below, but common welding types include:

- MIG welding

- TIG welding

- Spot welding

- Laser welding

Design for Weldability

- Match welding process to material thickness

- Avoid excessive heat input

- Design joints that minimize distortion

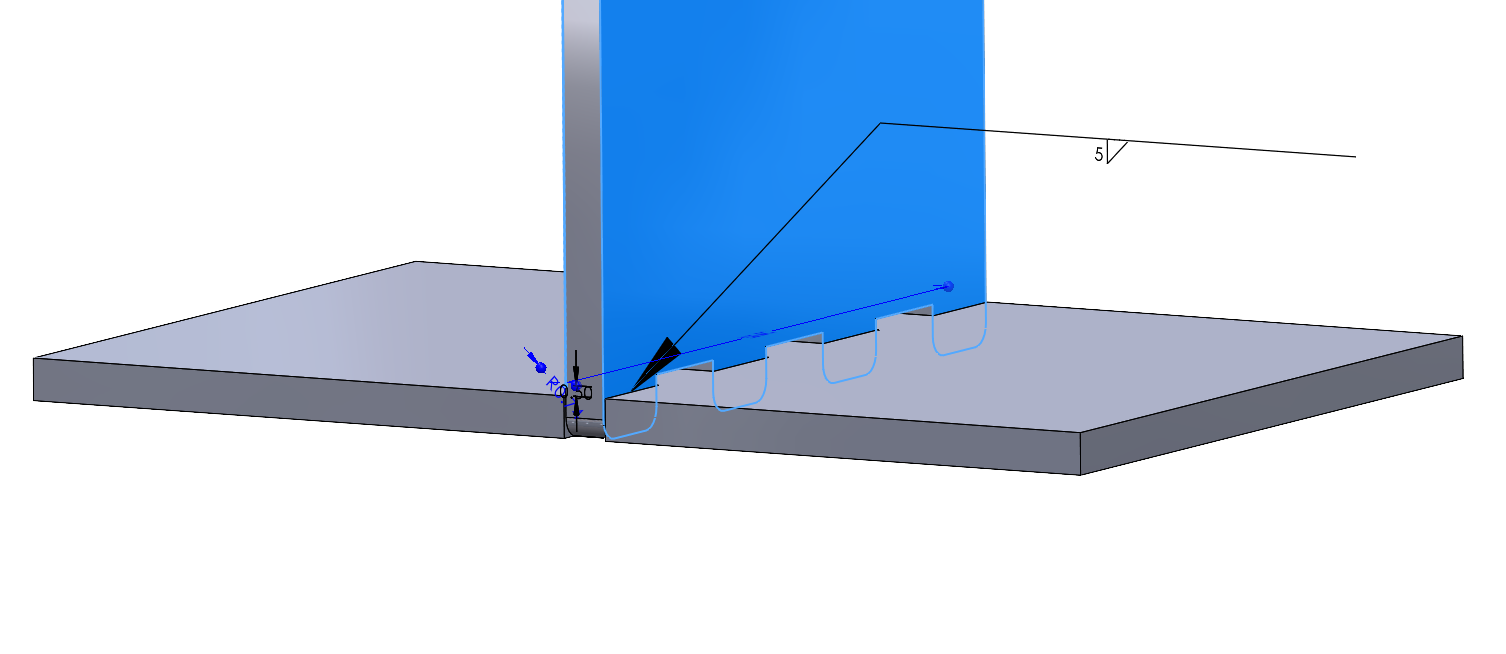

Tabs and Slots

Laser‑cut tabs and slots can:

- Improve alignment

- Reduce fixturing

- Speed assembly

They must be designed to avoid stress concentrations.

Mechanical Fasteners

Why Fasteners Persist

Mechanical fasteners remain common in product design because they offer predictable strength, broad availability, and straightforward serviceability. They are often the safest option when loads are high, regulatory requirements apply, or disassembly is expected over the product’s life.

That said, fasteners add bill-of-materials cost, assembly time, and access constraints, making them a frequent target for DFMA optimization.

Mechanical fasteners remain common because they offer:

- Predictable strength

- Easy sourcing

- Serviceability

- Design flexibility

However, they add BOM cost and assembly time.

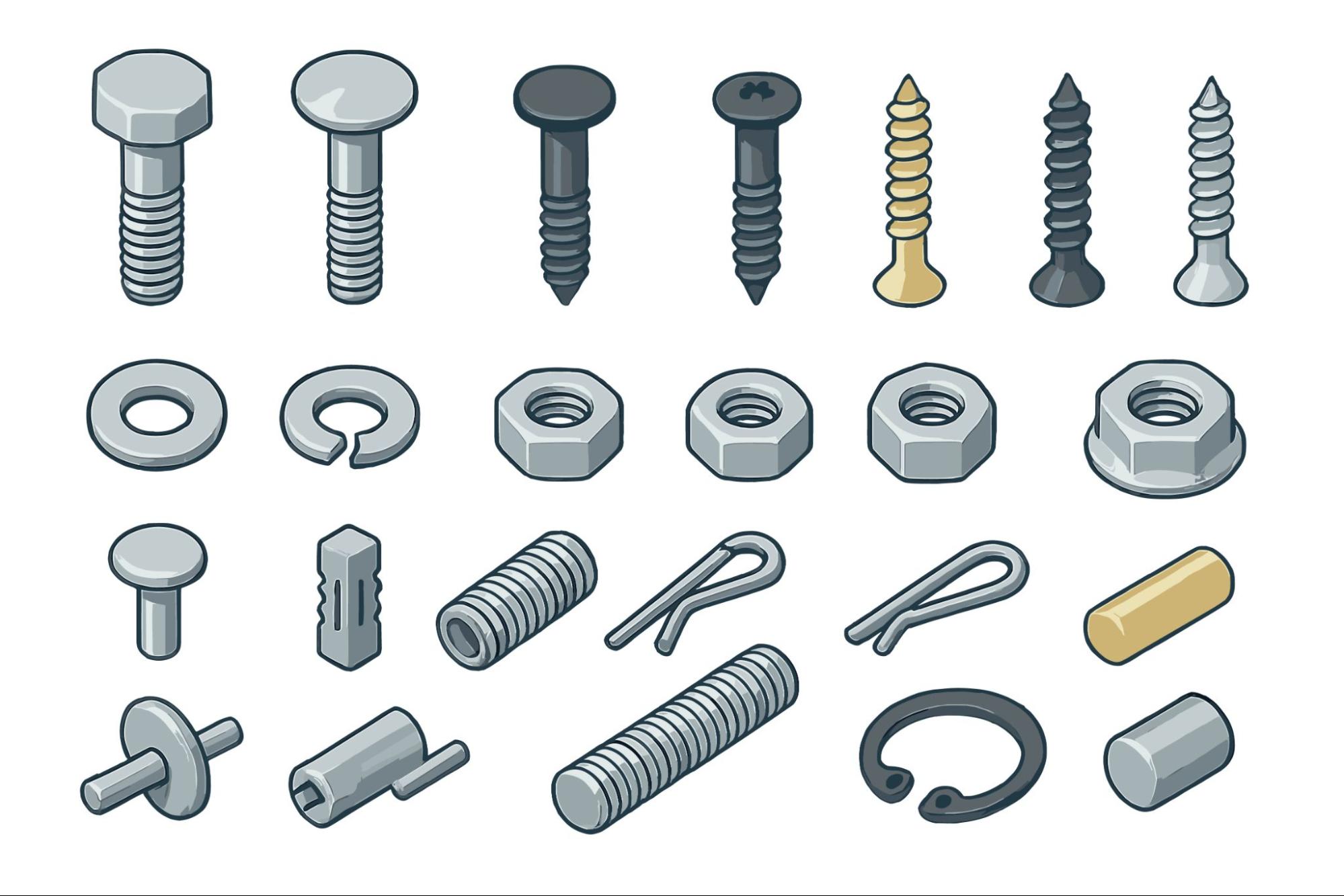

Common Fastener Types

- Screws and bolts

- Nuts and washers

- Rivets

- Dowel pins

- Threaded inserts

- Clips and retainers

Assembly‑Focused Fastener Design

- Design joints so fasteners provide clamping, not alignment

- Ensure tool access in the assembled state

- Avoid over‑specifying fastener grades

- Consider galvanic corrosion between materials

Fasteners in Plastics

- Use inserts for repeated assembly and reliable pull-out strength

- Use self‑tapping screws to reduce cost, but avoid them for long‑life joints

- Design adequate boss wall thickness

Adhesives

Why Use Adhesives

Adhesives enable joining dissimilar materials, distribute stress more uniformly than point fasteners, and provide vibration damping. They also support clean external surfaces without visible hardware, making them increasingly common in electronics, consumer products, and lightweight structures.

Adhesive Categories

- Structural (epoxies)

- Semi‑structural (urethanes, cyanoacrylates)

- Non‑structural (hot melts, pressure‑sensitive tapes)

Surface Preparation

Surface preparation is perhaps the most critical factor in adhesive success:

- Clean oils and contaminants

- Increase surface energy when needed

- Control bond‑line thickness

Assembly Considerations

- Cure time affects take time (production rate)

- Inspection methods must be defined

- Rework strategy should be planned

A Repeatable Assembly Design Workflow:

- Define joint requirements

- Select primary joining method

- Design location and fit strategy

- Review tolerance stack‑up

- Validate with prototypes

- Perform DFMA review before release

DFMA checkpoint (copy/paste into your design reviews)

Conclusion: Assembly Is a Design Discipline

Assembly success is rarely about choosing the “best” joining method in isolation. It is about making early, intentional design decisions that balance cost, manufacturability, performance, and scalability.

By applying DFMA principles, understanding joining methods, and designing fits intentionally, teams can create products that assemble faster, cost less, and scale with confidence.

Ready to Build With Confidence?

Designing for assembly is only half the equation—executing it reliably at scale is where experienced manufacturing partners matter.

Fictiv helps engineering teams turn DFMA‑driven designs into production‑ready assemblies, with global manufacturing capabilities across CNC machining, injection molding, sheet metal fabrication, and secondary operations. From early prototypes to full-scale production, Fictiv’s engineers help identify assembly risks early, optimize part design, and streamline the path to market.

Fictiv has partnered with Misumi to provide custom manufacturing and assembly, as well as standard off-the-shelf components, from a single source.

Contact us to learn how Fictiv can support your next assembly-focused project at scale.