Time to read: 9 min

Design for Serviceability (DFS) is an engineering approach that ensures products can be efficiently inspected, maintained, repaired, and upgraded throughout their operational life using accessible layouts, modular components, and standardized interfaces.

Product development often focuses on performance and quality at launch, while long-term success depends just as much on how easily the product can be maintained and serviced.

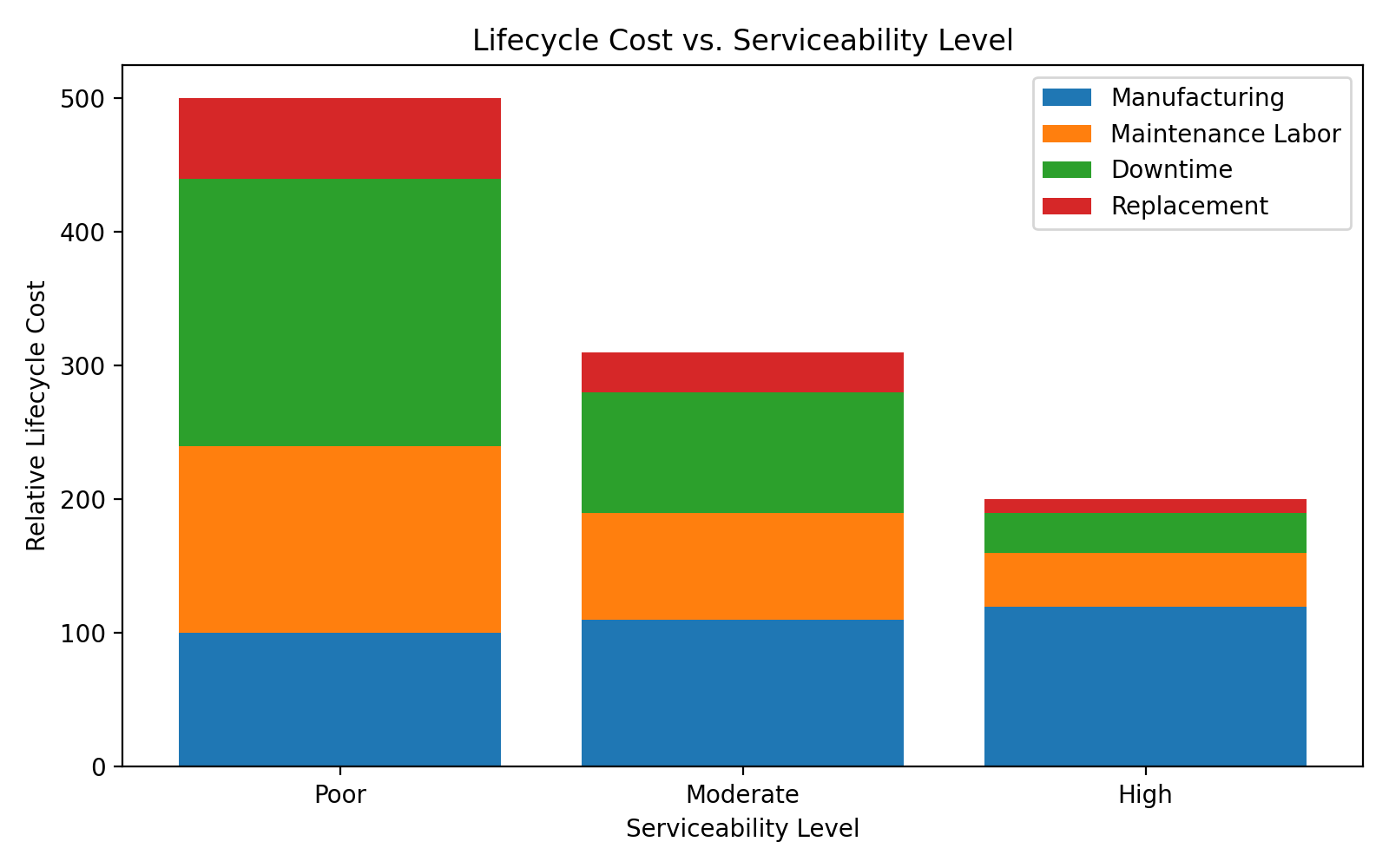

Poor serviceability rarely shows up as a single failure. Instead, it appears as long repair times, extended downtime, repeated service interventions, frustrated technicians, and dissatisfied customers. A familiar example is vehicle ownership, where higher maintenance and service costs over time can offset a lower upfront price.

Several trends have pushed serviceability from a “nice-to-have” to a core design requirement. Products are staying in service longer. The combined cost of labor and downtime can rival—or exceed—the cost of replacement, especially for capital equipment. More systems are now deployed in remote or distributed environments where access is limited and service visits are expensive.

Replacing a $5 fan should not require removing a $5,000 assembly. Yet many products force a similar outcome—turning minor failures into costly downtime. Applying Design for Serviceability (DFS) principles reduces mean time to repair (MTTR), improves uptime, and lowers total cost of ownership without compromising performance.

This article outlines practical, engineering-focused principles for serviceability design and shows how early design decisions shape maintenance effort, lifecycle cost, and system uptime.

Speaking of services, have you seen ours? Take a look at our manufacturing capabilities.

What Is Design for Serviceability (DFS)?

Design for Serviceability is the practice of engineering products so that maintenance and repair activities can be performed quickly, safely, and consistently using commonly available tools and technicians with appropriate training.

Service activities include inspection, diagnostics, troubleshooting and repair, component replacement, calibration, and upgrades. Serviceability is often assessed using metrics such as mean time to repair (MTTR), which is the period a product is unavailable due to diagnosis, repair, component replacement, and reassembly—not just the repair action itself.

Design for Serviceability brings together reliability, maintenance, and repair considerations into a unified design approach focused on in-service behavior. Reliability engineering addresses the failure frequency, while serviceability assesses the efficiency of maintenance and repair when intervention is required.

Accessible layouts, modular architectures, and clear diagnostics help preserve the benefits of good reliability design over the product’s operational life. Without them, even robust systems become expensive and difficult to support.

Design for Serviceability sits alongside other Design for Excellence (DFX) practices such as Design for Manufacturing and Design for Assembly, reflecting the same principle: early design decisions disproportionately determine downstream cost, risk, and performance.

Core Principles of Design for Serviceability

Effective Design for Serviceability relies on the following set of principles applied early in the design process, when changes are less expensive and more impactful.

Accessibility

Components that require inspection or replacement should be visible, reachable, and removable without disassembling unrelated systems. Adequate clearance for hands, tools, and line of sight reduces MTTR even for low-cost parts.

Modularity

Partition products into replaceable subassemblies with clear mechanical and electrical interfaces. Module boundaries should align with expected failure, wear, or upgrade points so components can be replaced without disturbing surrounding systems or compromising thermal paths, structural integrity, or alignment. This enables faster module swaps while preserving overall system performance.

Standardization

Limit fastener types and connector styles to reduce errors, simplify toolkits, and improve parts availability. Standardized interfaces shorten MTTR by making replacement components easier to source and service procedures more repeatable and efficient across product variants.

Diagnostics and Feedback

Provide actionable indicators such as test points, LEDs, fault codes, logs, or telemetry to guide service decisions without trial-and-error. Clear diagnostics reduce unnecessary disassembly and repeat service visits.

Safety and Ergonomics

Design for repeated service without injury or damage to either the product or the technician. Where possible, avoid sharp edges, awkward reaches, high-preload fasteners, and assemblies that become unsupported or unstable during disassembly.

These principles don’t require sophisticated technology, but they do require intentional prioritization early in the design process. Layout decisions, interface strategies, and access provisions are far easier to implement before designs are locked. More advanced features—such as embedded diagnostics or telemetry—are most effective when built on a fundamentally serviceable mechanical and architectural foundation.

The Business Case for DFS: Lifecycle Cost, Uptime, and Customer Experience

In practice, serviceability influences a broader set of performance and cost metrics tracked by engineering, operations, and service teams throughout a product’s life.

How Design for Serviceability Influences Lifecycle Metrics

The table below summarizes how Design for Serviceability directly influences common lifecycle and reliability metrics used in engineering and operations.

| Metric | What It Measures | How Design for Serviceability Influences It |

| MTTR (Mean Time to Repair) | Time required to restore a system during maintenance or after a fault | Accessible components, modular subassemblies, standardized fasteners, and explicit fault indicators reduce diagnosis time and disassembly/reassembly effort |

| MTBF (Mean Time Between Failures) | Average operating time between required interventions | While primarily driven by design robustness and operating conditions, improved serviceability supports preventive maintenance adherence, helping preserve expected reliability over time |

| Uptime / Availability | Percentage of time the system is performing its intended function | Faster diagnosis and repair reduce downtime for assets intended to operate unattended for long periods, such as remote equipment or fixed infrastructure |

| Lifecycle Cost (Total Cost of Ownership) | Total cost over the product’s usable life | Lower labor hours per service event, fewer escalations to specialized service, reduced training effort, and higher first-time service success rates |

Two systems can have identical reliability yet very different lifecycle costs depending on how quickly issues can be identified and corrected. Insufficient access, non-modular layouts, and inconsistent interfaces extend service time and increase downtime even when failure rates are low.

From the customer’s perspective, these effects compound. Long repair times lead to lost productivity, missed availability commitments, and reduced confidence in the product—outcomes that warranty terms alone rarely offset.

For these reasons, Design for Serviceability must be addressed early in product development. Once enclosure layouts, module boundaries, and interface strategies are fixed, most service time, cost, and operational risk are effectively determined. Designing for access, replacement, and diagnosis is not a late-stage refinement; it is a fundamental design choice with long-term economic consequences.

Mechanical Design Guidelines for Serviceable Hardware

Serviceability is largely determined by mechanical design choices that affect access, disassembly, and reassembly during routine maintenance and repair. Even small layout and fastening decisions can significantly influence service time and error rates.

Design guidelines to keep in mind:

- Access panels should open without disturbing unrelated components.

- Fasteners should be visible, captive where appropriate, and consistent in size and head type.

- Components that are removed repeatedly should use robust threads, inserts, or metal bosses rather than bare plastic.

- Cable routing should include intentional service loops (engineered slack) and strain relief so components can be repositioned during service without stressing connectors.

- Joint selection is equally important; adhesives and welds may simplify assembly but usually prevent repair, while screws, clips, and self-clinching fasteners support repeatable disassembly and controlled reassembly.

Modularity, Architecture, and Part Partitioning

Poor serviceability often occurs when a single worn or failed component is buried behind unrelated systems, forcing unnecessary teardown. Intentional modularity groups these components by service frequency and wear risk rather than function alone.

Items such as filters, batteries, fans, seals, sensors, and electronics should be placed in dedicated service zones or carriers that allow direct replacement without disturbing surrounding assemblies. Designing around these service realities reduces downtime and helps extend system life by keeping repair economically viable.

Clear module boundaries make it obvious where a serviceable unit begins and ends—interfaces are standardized, fasteners are accessible, and removal does not require partial disassembly of adjacent modules. Unclear boundaries increase service time and error risk. Clear boundaries also simplify spares and upgrades.

Design for Diagnostics and Predictive Maintenance

Without diagnostics, service becomes guesswork. Effective Design for Serviceability includes features that guide troubleshooting before an enclosure is opened, such as test points, LEDs, fault codes, onboard logs, or telemetry connected to external monitoring systems.

Predictive maintenance builds on this foundation by leveraging software and data trends—such as rising current draw or temperature drift—to schedule service before failure. Diagnostics should indicate likely causes, not just symptoms; for example, distinguishing a sensor fault from a wiring issue.

Serviceability, Sustainability, and Right to Repair

Serviceability supports sustainability by extending useful product life and reducing waste. Modular designs enable targeted replacement instead of full-system disposal.

As right-to-repair regulations expand, products are increasingly expected to be serviceable using non-proprietary tools and documented procedures. DFS therefore becomes both a compliance consideration and a cost-control strategy, supporting more circular product lifecycles.

Practical Design for Serviceability Checklists for Engineers

During concept development and layout

During mechanical design

During design validation

How Digital Manufacturing enables Design for Serviceability

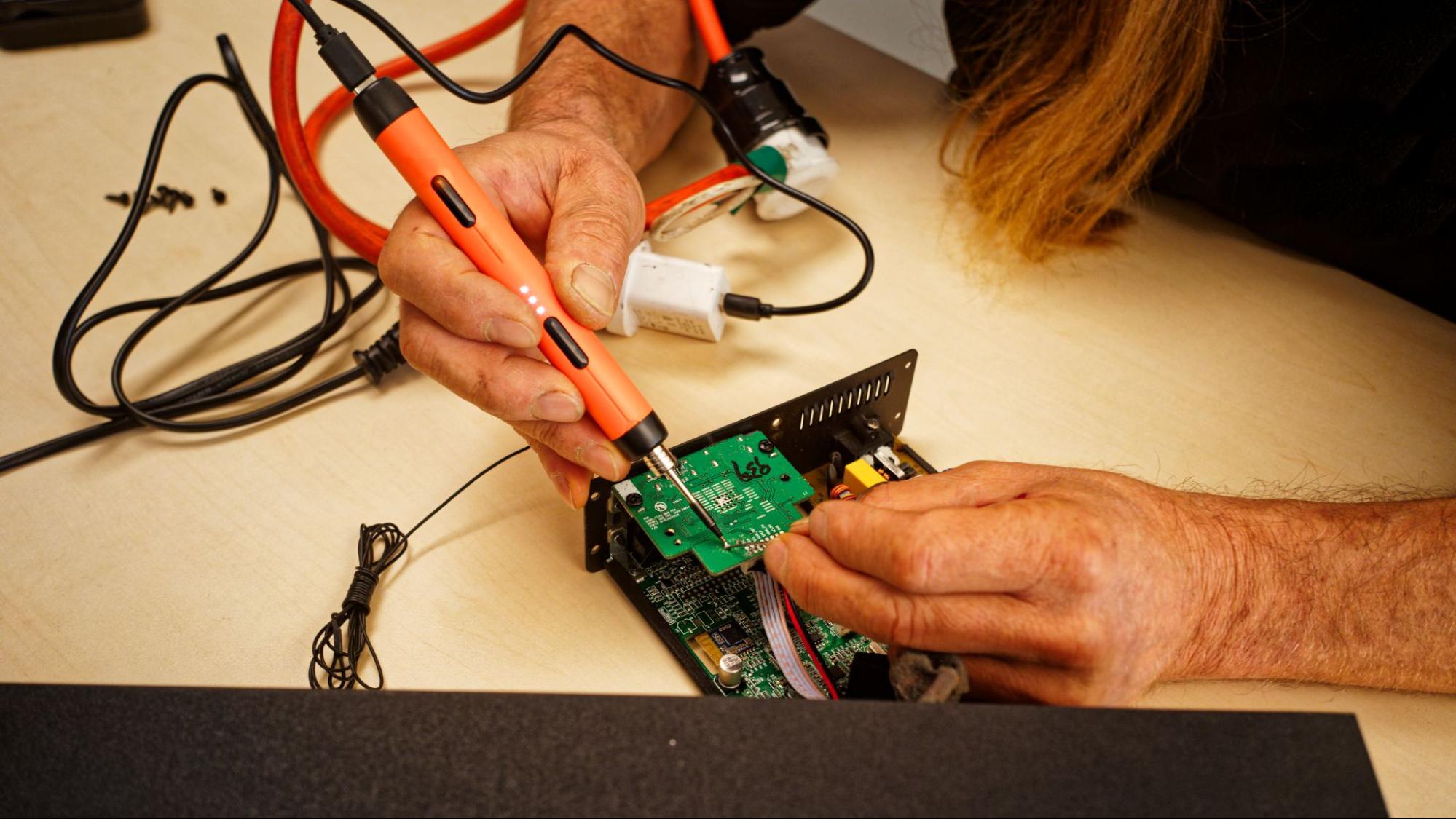

Serviceability improvements are easiest to validate during prototyping. Fast-turn CNC, sheet metal, and injection-molded parts enable early testing of access envelopes, tool clearances, and module swaps.

Digital manufacturing platforms support DFS by allowing rapid iteration and feedback that account for disassembly and service access, not just initial assembly.

Fictiv supports teams designing serviceable hardware by validating mechanical layouts, building functional prototypes, and sourcing replacement parts throughout the product lifecycle.

Serviceability Is Designed In From the Start, Not Added Later

Design for Serviceability is more than a checklist. It is a mindset that integrates accessibility, modularity, standardization, diagnostics, and safety into product design from the earliest stages.

Products engineered with these principles are easier to maintain, faster to repair, and more reliable over their operational life. Implementing DFS reduces downtime, lowers lifecycle costs, and supports sustainability by extending the usable life of hardware.

Building hardware that has to live in the field for years? Fictiv’s digital manufacturing platform helps you prototype, test, and refine serviceable designs quickly, from CNC-machined components to sheet-metal enclosures and molded parts. Upload your CAD model to get DFM insights and a fast quote.