Time to read: 10 min

Mechanical fasteners have been around for millennia, with basic forms dating back to 3500 BCE in Mesopotamia. To this day, fasteners remain one of the most foundational joining methods in engineering, even as other assembly and joining methods, such as adhesives and welding, continue to advance. From aerospace assemblies to consumer electronics, mechanical fasteners offer advantages that alternative assembly methods cannot: predictable strength, simple sourcing, easy installation, and repeatable serviceability.

In product development, mechanical fastening plays a critical role during prototyping and production:

- Prototypes: Quick assembly and disassembly for iteration.

- Production Assemblies: Proven joint reliability, controlled preload, and standardized hardware.

- Field-Serviceable Components: Replaceable parts and accessible repairs, which are vital for industries like automotive, medical devices, and industrial equipment.

Mechanical fasteners also strongly support Design for Assembly (DFA) as they enable:

- Simplified component interfaces

- Consistent assembly processes

- Reduced cycle times

- Lower tooling costs

- Clear paths for automation

While alternative joining methods may be better suited to specific use cases, mechanical fasteners are indispensable in manufacturing due to their strength, versatility, and compatibility with design constraints.

This article will further discuss mechanical fasteners—the common types, applications, design considerations, and typical problems.

What Are Mechanical Fasteners?

Mechanical fasteners are hardware components that join two or more parts by applying tension, compression, friction, or an interference (press) fit. They can be removed, replaced, or permanently deformed depending on the type and application.

Fastener Classification

Fasteners are broadly categorized by their intended lifespan and connection mechanism. But generally fall into the following categories:

Permanent vs. nonpermanent

- Permanent: Rivets, some pins, crimped or deformed fasteners

- Nonpermanent: Screws, bolts, nuts—intended to be reused

- Semipermanent: Threaded inserts, dowel pins, snap fits

Threaded vs. unthreaded

- Threaded: Bolts, screws, inserts

- Unthreaded: Rivets, pins, clips, snap fits

Understanding Fastener Loads

Engineers must design for the three primary load directions:

- Tensile Loads (Axial): Pulling along the axis of the fastener.

- Shear Loads: Sliding forces perpendicular to the axis.

- Combined Loading: Most real joints encounter both.

For optimal joint reliability, bolts and screws should primarily carry tension (clamping the joint surfaces together), while the joint interface itself carries the shear load via friction between the clamped parts. Poor load-path alignment—where fasteners are incorrectly stressed in shear or where friction is inadequate—is a leading cause of mechanical fastener failure.

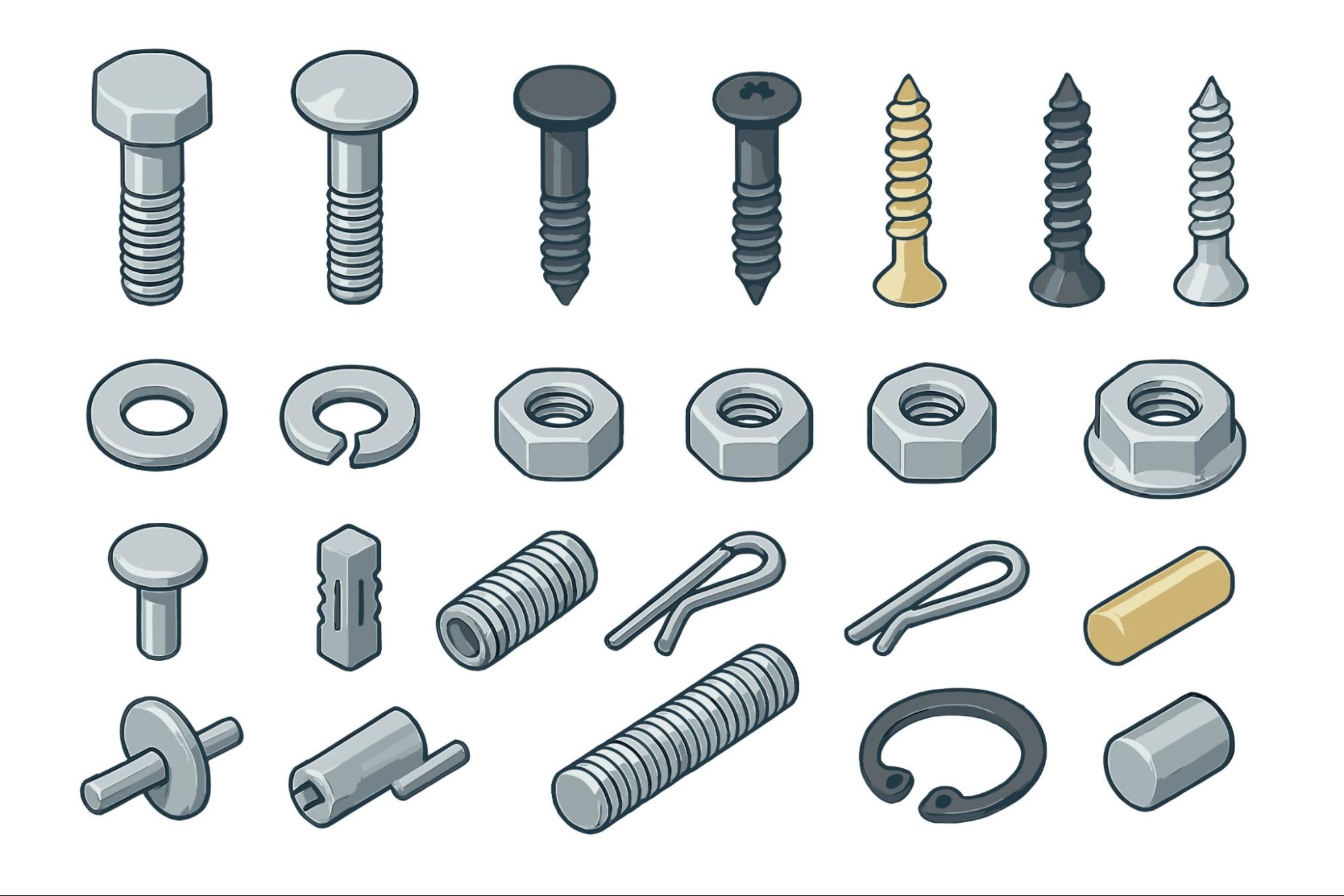

Common Types of Mechanical Fasteners

Mechanical fasteners cover a broad range of hardware. These are the most widely used fastener categories in engineering and manufacturing:

Bolts & Screws

Bolts and screws provide high tensile strength, predictable preload (the initial tension applied to a bolt when tightened), and repeatable performance. They’re available in nearly endless head styles, drives, materials, and coatings.

- Bolts work with nuts to affect clamp load across multiple components.

- Screws are typically inserted into a threaded hole, or can be self-threading.

Nuts & Washers

Nuts mate with bolts, while washers spread clamp load and protect surfaces. Key washer types include:

- Flat washers: Increase bearing surface

- Lock washers: Resist vibration loosening of fasteners

- Fender washers: Large outer diameter for soft materials

There are also various types of nuts, including:

- Hex nuts: Versatile and wrench-friendly

- Flange nuts: Integrated washer for load distribution

- Lock nuts: Contain an insert (typically nylon) for vibration resistance

- Wing nuts: For hand tightening

Rivets

Rivets produce permanent joints, especially in sheet metal fabrication, aerospace skin panels, and large structures. Because they don’t require threads, rivets are lightweight, cost-effective, and easy to install. They also provide excellent fatigue resistance.

Pins & Dowels

Pins are ideal when accurate alignment or resisting shear is the primary goal. They may be straight, tapered, slotted, or coiled, depending on the required flexibility or fit.

Threaded Inserts

Inserts reinforce threads in materials that would otherwise strip, especially in plastics and aluminum. They can be press-fit, heat-set, ultrasonic, mold-in, or helical wire-style.

Snap Fits & Clips

Used heavily in consumer products, snap fits allow rapid assembly with little or no hardware. Clips and retainers—often made from plastic or metal, such as spring steel—serve similar functions as snap fits but for moderate loads or repeated use.

Table 1 provides a quick comparison between the different types of fasteners, how they’re joined, the direction in which loads are applied, and how they are removed.

Table 1: Comparison of Different Types of Mechanical Fasteners

| Fastener Type | Joint Type | Load Type | Removability |

| Bolt + Nut | Threaded | Tensile + Shear | Reusable |

| Screw | Threaded | Tensile | Reusable |

| Rivet | Deformed | Shear | Permanent |

| Dowel Pin | Interference | Shear | Semi-permanent |

| Snap Fit | Elastic Interlock | Shear + Tension | Reusable (limited) |

| Clip/Retainer | Elastic/Spring | Light shear | Reusable |

Table 2 shows the different characteristics of various fasteners—from their applications to their advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Different Characteristics of Mechanical Fasteners

| Category | Materials | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

| Bolts & Screws | Steel, Stainless | Metal assemblies | High strength | Needs access to both sides |

| Rivets | Aluminum, Steel | Aerospace, sheet metal | Lightweight, permanent | Nonreversible |

| Inserts | Brass, Stainless | Plastics | Reinforces threads | Requires heat/press install |

| Pins/Dowels | Steel, Plastic, Wood | Fixtures, alignment | High shear | Fixed position |

| Clips/Snap Fits | Plastic, Spring Steel | Consumer products | Fast assembly | Limited strength |

Design Considerations for Mechanical Fasteners

The successful performance of a mechanical fastener relies on more than just its material or classification, so product engineers must take a holistic approach by optimizing their fastener selection and implementation. This strategy is based, among other things, on five critical factors: fastener and component material compatibility, load paths, torque and preload, and thread engagement.

Material Compatibility

Use compatible materials to avoid galvanic corrosion, especially in marine, outdoor, or humid environments.

Load Path Alignment

Ensure fasteners are placed so:

- Tensile forces load the fastener axially.

- Shear forces act through the joint, not the bolt shank.

- Bending of fasteners is minimized.

Torque and Preload

Most fasteners require torque to reach a clamp force of 65–80% of the fastener’s proof load. Too little torque risks long-term loosening; too much risks stripping or breaking. The text below describes a simple preload example.

For a steel bolt with:

- Diameter: M6

- Proof load: ~700 MPa

- Tensile stress area: ~20 mm²

Proof load = 700 MPa × 20 mm² = 14,000 N

Target preload (of 75%) = 0.75 × 14,000 = 10,500 N

Torque needed ≈ preload × thread friction factor

≈ 7–8 N·m (typical for lubricated M6)

Understanding this relationship helps prevent both over-tightening and loose joints. Keep in mind that torque-preload relationships vary widely (± 25–30%) due to friction coefficient variations. A torque wrench is an excellent tool for setting and controlling specific torque values for fasteners.

Thread Engagement

The ideal thread engagement length varies depending on the materials being assembled. Adequate thread engagement length is critical to ensure sufficient shear strength in the female threads of the assembled parts. Engage threads to a minimum depth of:

- 1X diameter in steel.

- 1.5X diameter in aluminum.

- 2X diameter in plastics.

Spacing & Edge Distance

Having adequate spacing and edge distance between assembled parts helps ensure that the bond between components is secure. Improper spacing can lead to insufficient clamp force between parts when spacing is too large, or damage (part cracking and distortion) when spacing is too close. Therefore, use the spacing and edge distance guidance below for fastening parts.

Minimum spacing: ≥ 2X fastener diameter

Edge distance: ≥ 1.5X diameter

Vibration Resistance

When it comes to threaded fasteners, vibration can cause fasteners to slowly lose preload and clamping force between parts. The measures listed below help maintain preload in dynamic environments.

- Nylon-insert lock nuts

- Lock washers

- Threadlocker adhesives

Table 3 shows some important design considerations and guidelines for addressing them.

Table 3: Mechanical Fastener Design Considerations

| Factor | Guideline | Purpose |

| Material Compatibility | Avoid galvanic corrosion | Durability |

| Load Path | Align the fastener with the tension | Avoid bending |

| Torque & Preload | 65–80% proof load | Maintain clamp force |

| Thread Engagement | 1–2X diameter (depending on the materials of the parts being assembled) | Prevent stripping |

| Spacing/Edge Distance | ≥ 2X diameter | Prevent cracks |

| Vibration Resistance | Lock washers, threadlocker | Joint integrity |

Permanent vs. Nonpermanent Fasteners

Selecting the right fastener type depends heavily on whether your assembly needs to be disassembled later. Table 4 shows the different types of permanent vs. nonpermanent fasteners, their applications, advantages, and disadvantages.

Table 4: Permanent vs. Nonpermanent Fasteners

| Type | Applications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Permanent (Rivets, Welding) | High-load structures | Very strong | No rework |

| Nonpermanent (Bolts, Screws) | Serviceable assemblies | Reusable | May loosen |

| Semipermanent (Inserts, Snap Fits) | Plastic housings, etc. | Low cost | Limited cycles |

Permanent joints shine in structural contexts (such as transportation, construction, or heavy machinery), while nonpermanent fasteners dominate consumer electronics and automotive components.

Mechanical Fastening vs. Other Joining Methods

There are other joining methods beyond mechanical fastening techniques that each have their own advantages. Such alternative joining methods include adhesive bonding, welding, and heat staking. Table 5 compares mechanical fastening vs. other joining methods.

Table 5: Mechanical Fastening vs. Other Joining Methods

| Joining Method | Strength | Speed | Cost | Reworkability | Best For |

| Mechanical Fastening | High | Moderate | Low-Med | High | Metal, plastics |

| Adhesive Bonding | Moderate | Fast | Low | Low | Mixed materials |

| Welding | Very High | Slow | High | None | Metals |

| Heat Staking | Medium | Moderate | Medium | Low | Plastic + metal |

| Snap Fits | Low | Fast | Very Low | Moderate | Plastic enclosures |

Because of their balance of strength, cost, and serviceability, mechanical fasteners remain the most flexible joining method for engineered products.

Environmental & Material Considerations

Choosing the right material for fasteners goes beyond strength. It’s also important to consider how the mechanical fastener material reacts to certain environmental conditions, such as temperature, corrosion, and chemicals. Listed below are some important environmental considerations.

Corrosion Resistance

Corrosion resistance is an important consideration when choosing mechanical fasteners. If a fastener corrodes, the clamp strength between mating components could be lowered and lead to part failure. Therefore, selecting appropriate fastener materials or finishes that resist corrosion helps ensure the longevity of assembled parts. Consider using some of the materials below for corrosion resistance:

- Stainless steel: Best for water, sweat, or food-safe environments

- Zinc-plated steel: Suitable for indoor applications

- Aluminum: Lightweight, corrosion-resistant; commonly used in aerospace, automotive, and medical devices

Surface treatments of fasteners, such as those listed below, can also help guard against corrosion:

Temperature and Creep

When it comes to high temperatures, it’s important to consider creep in mechanical fasteners. Creep is the expansion of a material due to heat, which, especially in plastic fasteners, can weaken threads. This is why threaded inserts are commonly used instead of self-tapping screws in electronics, appliances, and automotive systems.

Chemical Compatibility

Designers must address chemical compatibility as various substances can significantly degrade common engineering materials. Materials such as nylon, zinc-plated surfaces, and even certain stainless steel grades are susceptible to chemical attack.

It is essential to check compatibility when the product will be exposed to solvents, lubricants, coolants, or intense UV exposure, as these can cause cracking, corrosion, or material failure over time.

Common Mechanical Fastener Problems and Solutions

Even well-designed assemblies still fall victim to problems with mechanical fasteners. Understanding common mechanical fastener failure modes helps engineers create more reliable assemblies from the start. Table 6 describes some common mechanical fastener challenges, their causes, and how to resolve them.

Table 6: Common Mechanical Fastener Challenges

| Problem | Likely Cause | Solution |

| Fastener loosening | Vibration, low torque | Lock nuts, threadlocker |

| Corrosion | Dissimilar metals | Coatings, stainless steel |

| Stripped threads | Overtightening | Follow torque specifications |

| Part cracking | Bad edge distance | Increase spacing |

| Uneven clamping | Mixed torque | Use a torque wrench |

| Fastener fatigue | Cyclical loading applied to fasteners | Use larger fasteners or vibration dampers |

Integrating Mechanical Fasteners into Product Design

Well-designed assemblies integrate mechanical fasteners early in the design process, not during the final engineering stages. From early CAD integration and Design for Assembly (DFA) considerations to using simulation software, engineers can determine how fasteners are incorporated into a design and what impact they have. Listed below are some of the methods for integrating mechanical fasteners early in design.

Early CAD Integration

Successful integration of mechanical fasteners begins during the initial Computer-Aided Design (CAD) phase. For example, designers must meticulously consider the boss sizes required for various screws to ensure proper thread engagement and material integrity. Additionally, tool access and driver clearance must be planned to allow for efficient assembly, as neglecting this can lead to slow production or damaged components.

Accessibility & Serviceability

Designing for good accessibility and serviceability means ensuring that tools can easily reach the fasteners necessary for both initial assembly and future maintenance. It is critical to avoid awkward or complex disassembly sequences where technicians must remove numerous irrelevant parts just to reach the component requiring service.

Design for Assembly (DfA)

Following a Design for Assembly (DfA) approach minimizes complexity and cost. Strive to use the fewest number of fastener sizes possible to simplify inventory and tooling. Top-down fastening directions are generally preferred for ease of assembly. Moreover, ensure consistency and reliability by standardizing torque values across similar joints. Custom hardware should be avoided unless absolutely necessary; instead, use off-the-shelf components to simplify the supply chain and part assembly.

Digital Manufacturing Advantages

Modern digital manufacturing services are well-equipped to handle fastener integration. Sheet metal fabrication, CNC machining, and molding services routinely offer features like PEM hardware insertion, which securely anchors nuts or studs into sheet metal. They also provide precision features such as tapped holes and countersinks. High-volume assembly often utilizes automated torque application for consistency, with quality control including detailed QC inspection reports for joint integrity.

Fasteners in Rapid Prototyping

When creating rapid prototypes, especially with 3D-printed plastics, there are specific considerations for fasteners. Use thread-forming screws designed for plastics that create their own threads for quick assembly. For joints requiring greater durability or repeated cycles, brass inserts should be added to the boss features for longevity. It’s essential to avoid undersized bosses in 3D-printed parts, as these are prone to cracking when the screw is installed.

Hybrid Fastening Approaches

Hybrid joints strategically combine mechanical fasteners with structural adhesives to exceed the capabilities of either joint when used individually. This synergy provides superior performance characteristics, particularly in terms of fatigue life and vibration control.

Where Hybrid Joints Shine

Hybrid joints are best in applications that demand exceptional structural integrity and durability, with a high factor of safety. Key areas include automotive body panels—especially where light-weighting is critical—and composite-to-metal joints, which are notoriously difficult to bond. Hybrid joints are also standard in high-stress products like sporting equipment and are often specified for fatigue-critical aerospace assemblies.

Hybrid Joint Design Tips

Designing an effective hybrid joint requires assigning specific roles to each component. The adhesives should be used to ensure stress distribution across the joint area, which reduces stress concentrations. The fasteners, conversely, are best utilized to handle shear loads and provide immediate handling strength before the adhesive fully cures. It is critical to ensure the joint gaps precisely match the adhesive thickness specified by the manufacturer for optimal bond strength. Finally, the fasteners can be used as temporary fixtures to hold the components in place while the adhesive cures, eliminating the need for expensive external clamping tools.

Design Optimization with Mechanical Fasteners

Mechanical fasteners remain one of the most versatile, predictable, and cost-efficient joining methods in modern engineering. By understanding how mechanical fasteners behave under load, how different materials interact, and how to design for both performance and manufacturability, engineers can create assemblies that are strong, serviceable, and production-ready.

Whether you’re designing aerospace hardware, consumer electronics, medical devices, or industrial machinery, mastering mechanical fasteners is a key part of creating reliable products.

Need help designing or producing assemblies with mechanical fasteners? Fictiv provides CNC machining, sheet metal fabrication, injection molding, and off-the-shelf hardware installation with expert DFM feedback. Upload your CAD files to get started.